The man with the 132-pound scrotum: 5-year ordeal ends in 13-hour surgery

- Wesley Warren Jr. battled scrotal lymphedema, a rare lymphatic disorder, for over five years.

- His scrotum swelled to 132 pounds, restricting mobility and daily functions.

- A groundbreaking 13-hour operation removed more than 160 pounds of tissue.

Picture a 49-year-old man unable to walk without dragging a mass heavier than most people between his legs, a weight that grew unchecked month after month.

Wesley Warren Jr. entered the world on June 23, 1963, in Orange, New Jersey.

He grew up in a typical East Coast setting before heading west in the 1990s to Las Vegas, drawn by opportunities in the bustling city.

There, he took on various jobs, including security work back in New York and later scouting locations for pay phones and ATMs on commission.

Life seemed ordinary until one night in late 2008 changed everything. While asleep, Warren twisted his leg awkwardly and struck his testicles, triggering intense pain that faded by morning.

But the next day revealed something far worse: his scrotum had ballooned to the size of a soccer ball.

What began as a minor injury spiraled into a medical nightmare, raising questions about how such a simple accident could lead to years of isolation.

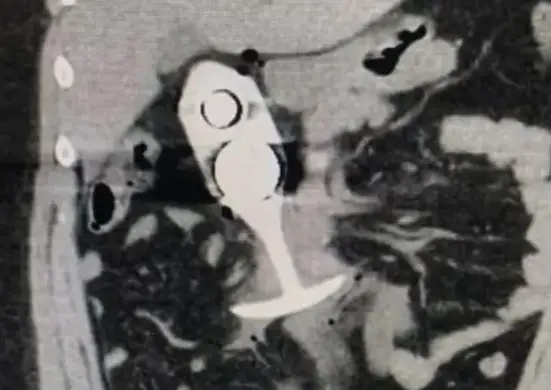

Doctors identified the issue as scrotal lymphedema, a condition where blockages in the lymphatic system trap fluid, causing extreme swelling in the genital area.

In tropical regions, this often stems from parasitic infections like lymphatic filariasis, which impacts around 120 million people globally, with many experiencing genital enlargement.

Yet in the United States, cases like Warren’s are exceedingly rare, typically linked to trauma, surgery, or radiation rather than parasites.

No infection showed up in his tests, pointing to the initial injury as the culprit.

The swelling progressed relentlessly, adding about three pounds each month, transforming his body in ways that defied easy solutions.

By early 2010, after an eight-week hospital stay and antibiotics that failed to help, Warren’s weight had climbed from 300 pounds to over 450 pounds, aggravating his existing high blood pressure and asthma.

Daily existence turned into a constant struggle. The massive scrotum, hanging below his knees, buried his penis and testicles beneath layers of skin, making urination a challenge—he had to aim through a narrow tunnel.

Sexual activity became impossible. To cover it, Warren fashioned clothing from an upside-down hooded sweatshirt, zipping it around the mass like makeshift pants.

Mobility suffered; he relied on a milk crate topped with a cushion to support the weight during short bus rides or walks.

At home, he propped it up similarly, confined mostly to his apartment in a low-income complex.

Public outings drew stares and laughter, turning him into what he called a “living and breathing freak show.”

But beneath the physical toll lay deeper questions: why did standard treatments fail, and how long could his body endure this unchecked growth?

Desperate for relief, Warren explored options. Initial consultations suggested Medicaid might cover a procedure, but risks included potential removal of his penis and testicles, a fate he dreaded for its impact on future relationships.

At Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, estimates pegged the cost at a seven-figure sum, far beyond his means as he lived on disability benefits.

The condition’s rarity compounded the problem—many physicians misdiagnosed it or advised weight loss, overlooking the lymphatic blockage.

In severe cases worldwide, scrotal lymphedema can reach grapefruit or basketball sizes, but Warren’s stood out as one of the largest documented in medical literature.

With infections looming as a life-threatening risk, he turned to unconventional avenues for help.

Media became his lifeline. In the fall of 2011, Warren appeared on The Howard Stern Show, sharing his story and setting up a PayPal account for donations under the email benefitballsack@yahoo.com.

A profile in the Las Vegas Review-Journal garnered over a million views, amplifying his plea.

He even featured in a sketch on Comedy Central’s Tosh.0. By November that year, he had raised $8,000, but an offer from The Dr. Oz Show for free surgery in exchange for exclusive rights fell through over concerns about complications.

As the mass continued expanding, weighing in at 132 pounds by 2013, Warren’s total body weight hit 552 pounds.

The veins within grew to a quarter-inch wide, heightening surgical dangers. Yet amid the despair, a breakthrough emerged that would test the limits of reconstructive urology.

In April 2013, Dr. Joel Gelman, director of the Center for Reconstructive Urology at the University of California, Irvine, stepped forward.

After hearing Warren’s appeal on Stern’s show, Gelman offered the procedure pro bono, provided Nevada Medicaid covered hospital expenses.

The operation, on April 8, lasted 13 hours and involved four surgeons. They made a T-shaped incision, carefully preserved the buried penis—hidden a foot deep—and excised the engorged tissue.

The removed mass totaled over 160 pounds, including fluid and smaller pieces, in a procedure fraught with risks from anemia and massive blood vessels.

Post-operation, Warren started physical therapy within a week and left the hospital in late April, recovering in a nearby nursing home.

For the first time in years, he slipped into normal underwear and pants, though adjusting to the lighter frame felt surreal.

He dreamed of simple pleasures like driving or dining out, but what unforeseen challenges might arise in his new life?

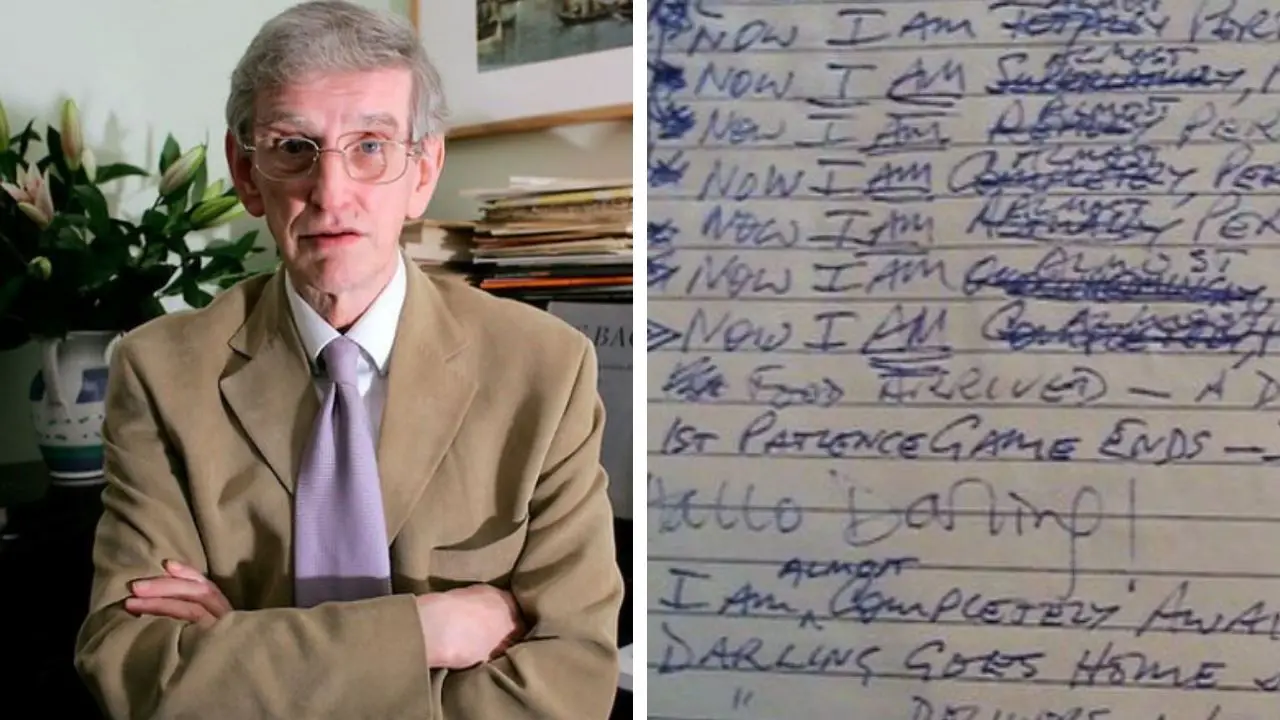

Documentaries captured the saga, drawing global eyes. British filmmakers from Firecracker Films followed Warren for Channel 4’s “The Man with the 10-Stone Testicles,” airing June 24, 2013, as part of the Body Shock series.

In the U.S., TLC broadcast it on August 19 as “The Man with the 132 lb Scrotum,” attracting viewers curious about this medical anomaly.

The UK episode drew nearly 4 million watchers, peaking at a 13 percent audience share and generating 76,636 tweets, ranking as the sixth most-tweeted program that week.

Australian audiences saw it on Seven Network in September under “The Man with the Biggest Testicles.”

These exposures not only highlighted Warren’s resilience but also sparked discussions on rare diseases, potentially encouraging others to seek treatment.

Still, the spotlight raised ethical debates: how does one balance privacy with the need for awareness in such intimate health battles?

Life after surgery brought renewed freedom. Warren, now able to move without the constant drag, purchased a new van and traveled to Los Angeles with his roommate, Joey Hurtado.

He returned to media spots, including Stern’s show, sharing updates on his progress.

Yet underlying health issues persisted—diabetes, heart problems—that had little to do with the lymphedema.

In a poignant twist, Warren’s story inspired another man, Dan Maurer from Michigan, who suffered a similar 100-pound condition and pursued surgery after learning of Warren’s case.

This ripple effect underscored the power of visibility in tackling underreported ailments.

Timeline of Key Events in Wesley Warren Jr.’s Journey:

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| June 23, 1963 | Born in Orange, New Jersey. |

| 1990s | Moves to Las Vegas for work opportunities. |

| Late 2008 | Injury triggers onset of scrotal lymphedema; swelling begins. |

| Early 2010 | Unsuccessful eight-week hospital treatment. |

| Fall 2011 | Appears on The Howard Stern Show; raises $8,000 in donations. |

| April 8, 2013 | Undergoes 13-hour surgery removing 160+ pounds of tissue. |

| June 24, 2013 | UK documentary airs, viewed by nearly 4 million. |

| March 14, 2014 | Dies at age 50 from heart attacks and diabetes complications. |

Warren’s passing on March 14, 2014, at University Medical Center in Las Vegas came after a five-and-a-half-week hospital stay marked by two heart attacks and infections tied to his diabetes.

At 50 years old, with no immediate family nearby, he left behind a legacy that Hurtado described as being “trapped by his own body for years.”

His case shone a light on scrotal lymphedema’s global toll, where treatments like complex decongestive therapy or surgery offer hope, but access remains limited in non-endemic areas.

In endemic regions, prevalence ties to filariasis, but Warren’s non-parasitic form highlights trauma’s role, prompting experts to call for better diagnostics.

As more cases surface, one wonders what undiscovered stories of endurance lie hidden in the shadows of rare medical conditions.