Gympie Gympie: Most dangerous plant in the world? One touch causes 9 months of pain

- Gympie-Gympie’s neurotoxin mimics spider venom, triggering intense pain signals in nerves.

- A single sting can lead to symptoms persisting for months or even up to two years.

- This shrub, up to 10 meters tall, thrives in Australia’s rainforests and poses risks to wildlife and humans.

Picture a shrub in the lush rainforests of north-east Australia where the slightest brush against its leaves injects a venom so potent that victims describe the sensation as simultaneous electrocution and acid burns, with effects that have prompted desperate acts among both people and animals.

The Gympie-Gympie, scientifically known as Dendrocnide moroides, stands out among poisonous plants for its unparalleled capacity to inflict suffering.

This member of the Urticaceae family, akin to stinging nettles but far more virulent, grows as a perennial shrub in the understory of tropical rainforests.

Its heart-shaped leaves, measuring 12 to 22 centimeters long and 11 to 18 centimeters wide, feature serrated edges and a pointed tip, attached to petioles of similar length.

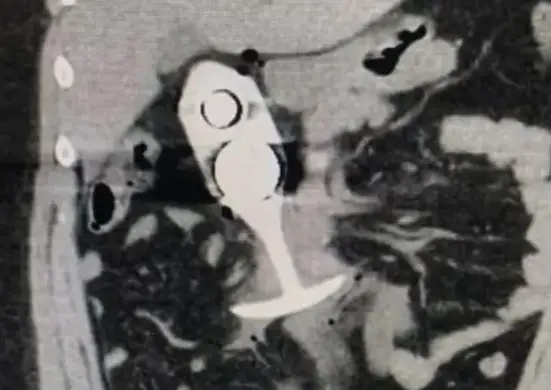

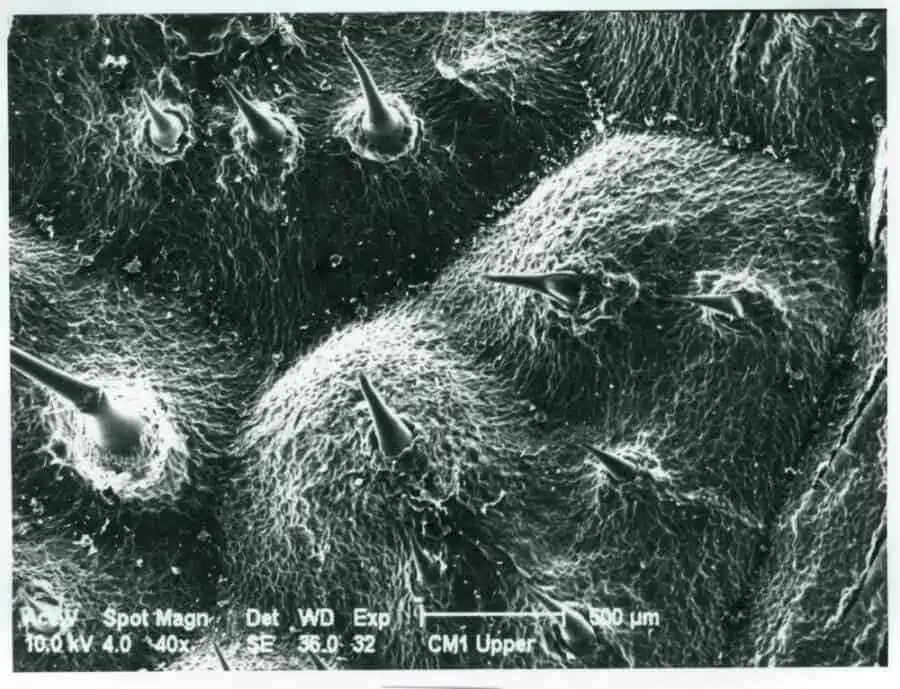

The entire plant, from stems to fruits, bristles with silica-based trichomes—hollow, needle-like hairs that break off easily upon contact, embedding in skin and releasing a cocktail of neurotoxins.

These structures, visible under electron microscopy as fine fuzz, shed readily, allowing airborne stings even without direct touch, much like pollen dispersing in the wind.

Endemic primarily to north-east Queensland, the plant extends its range southward to northern New South Wales, where it holds endangered status, and appears in parts of Indonesia and the Moluccas.

It colonizes disturbed areas quickly, such as riverbanks, road edges, or clearings from fallen trees, germinating in full sunlight after soil upheaval.

In these habitats, it reaches heights of up to 10 meters in mature forms, though it often flowers and fruits at under 3 meters.

The inflorescences, up to 15 centimeters long, bear both male and female flowers, blooming year-round with peaks in summer, leading to mulberry-like fruits that turn pink to light purple when ripe.

What elevates this stinging tree to the status of the most dangerous plant lies in its venomous arsenal.

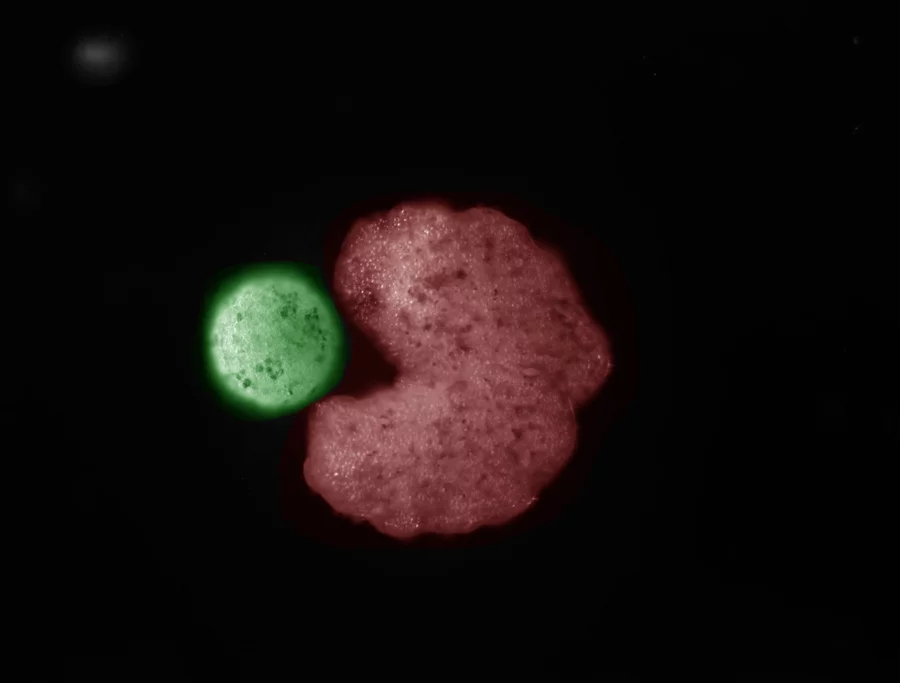

The trichomes act like hypodermic needles, injecting gympietides—small peptide molecules that structurally resemble toxins from spiders and scorpions.

These compounds bind to sodium ion channels in sensory neurons, preventing them from deactivating and thus prolonging pain signals far beyond typical irritants.

One key component, moroidin, a bicyclic octapeptide, contributes to the venom’s stability, ensuring effects linger long after initial exposure.

Unlike common nettle stings, which subside in hours, Gympie-Gympie contact causes immediate whitening and swelling at the site, escalating to severe burning within 20 to 30 minutes.

Victims report the agony as a throbbing vise grip combined with electrical shocks, often preventing sleep for days.

In severe instances, lymph nodes swell painfully, hives erupt across the body, and allergic reactions intensify with repeated exposures, sometimes necessitating steroid interventions.

Botanist Marina Hurley, who studied the plant extensively, likened the ordeal to being scorched by hot acid while electrocuted, noting flare-ups years later triggered by cold or minor irritations.

Such prolonged distress has earned it nicknames like “suicide plant,” reflecting rare but documented cases where the unrelenting torment led to self-harm.

I touched the world’s most painful plant!

Historical accounts underscore the plant’s peril. During World War II training in Queensland, ex-serviceman Cyril Bromley tumbled into a cluster of these shrubs, resulting in hospitalization where he was restrained to his bed, raging in delirium for days.

Another soldier, mistaking a leaf for toilet paper in the bush, endured such excruciating genital pain that he ultimately took his own life.

In 1963, forester Ernie Rider suffered stings to his face, arm, and chest, with the torment persisting until 1965, marking one of the longest recorded recoveries.

Animals fare no better; reports from the 19th century describe horses, driven mad by the stings, plunging off cliffs to their deaths, while dogs and other mammals have succumbed in isolated incidents.

Beyond humans, the Gympie-Gympie interacts dynamically with its ecosystem.

It hosts larvae of the white nymph butterfly, Idea leuconoe, and sustains insects like the nocturnal beetle Prasyptera mastersi and moth Prorodes mimica, which feed on its foliage despite the defenses.

Remarkably, the red-legged pademelon, a small marsupial, browses the leaves unharmed, suggesting immunity to the neurotoxins.

Birds consume the fruits, dispersing seeds through droppings and aiding propagation in fragmented habitats.

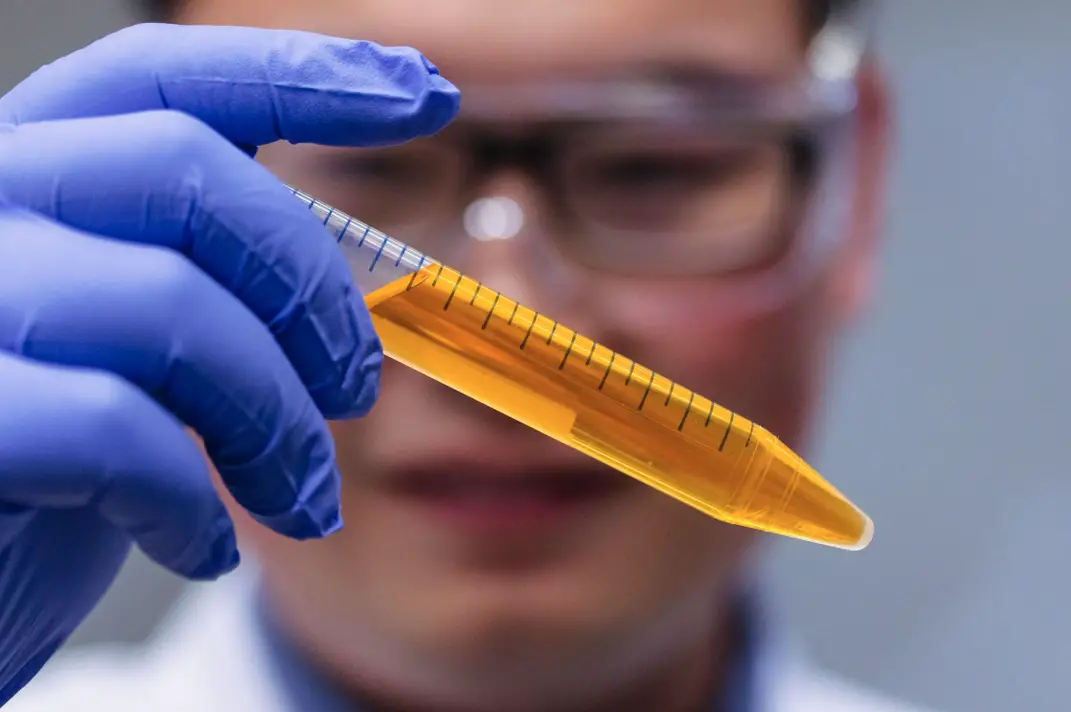

Scientific interest in this deadly flora has surged in recent decades.

Researchers at the University of Queensland identified the gympietides in 2020, revealing their potential to inform new analgesics by targeting pain pathways.

A 2023 study explored how these toxins could inspire non-opioid pain relief, given their precise activation of neuronal channels.

Earlier work isolated moroidin, but challenges in synthesizing it persist due to the plant’s hazards, limiting large-scale extraction.

In medical contexts, treatment focuses on immediate hair removal using wax strips or tape to prevent further toxin release, followed by analgesics, antihistamines, and in extreme cases, hospitalization for monitoring.

| Key Statistic | Detail |

|---|---|

| Maximum Height | Up to 10 meters |

| Leaf Dimensions | 12-22 cm long, 11-18 cm wide |

| Trichome Density | Covers entire plant surface, including fruits |

| Pain Onset Time | Intensifies within 20-30 minutes |

| Average Pain Duration | Days to months; up to 2 years in severe cases |

| Toxin Composition | Gympietides (peptide neurotoxins similar to arachnid venoms) |

| Geographic Range | North-east Queensland (approx. 100,000 sq km rainforest habitat), extending to Indonesia |

| Endangered Status | Rare in New South Wales, listed as endangered |

Intriguingly, despite its lethal reputation, the Gympie-Gympie offers a paradoxical boon: its achene fruits, encased in fleshy sacs, prove edible once the stinging hairs are meticulously stripped away.

Indigenous groups, including the Gubbi Gubbi people who named it, have long navigated this risk, but modern foragers rarely attempt it amid the dangers.

As studies delve deeper into its biochemistry, questions arise about whether this scourge of the rainforest might one day yield breakthroughs in managing chronic pain conditions that afflict millions worldwide.

What other secrets lie hidden in its venomous embrace?