Guatemala City’s Terrifying Sinkhole: Why the Earth Swallowed a Factory Overnight

On May 30, 2010, the ground beneath Guatemala City’s Zona 2 gave way in a matter of seconds, forming a gaping sinkhole that swallowed a three-story textile factory whole.

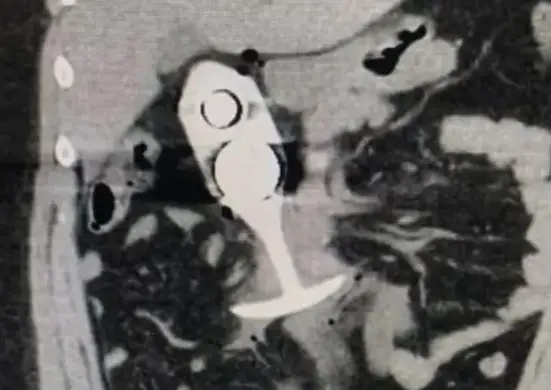

This wasn’t a gradual subsidence but a sudden, almost surreal collapse—a near-perfect cylindrical crater, 20 meters wide and 90 meters deep, that seemed to defy reality.

Residents stood in disbelief, staring into an abyss that had erased part of their neighborhood.

How could the earth open up so violently? Was this a freak act of nature, or did human oversight play a role?

The answers lie in a complex interplay of natural forces and systemic failures, revealing a city built on precarious ground.

The stage for this disaster was set by a convergence of events that began days earlier.

On May 27, 2010, the Pacaya Volcano, located just 30 kilometers south of Guatemala City, erupted, spewing ash and debris across the region.

This volcanic activity didn’t directly cause the sinkhole, but it played a critical role.

Ash clogged the city’s drainage systems, creating blockages that prevented water from flowing properly.

This added pressure to an already fragile underground infrastructure, setting the scene for catastrophe.

Then came Tropical Storm Agatha, the first named storm of the 2010 Pacific season, which battered Central America with relentless rains.

In Guatemala City, over a meter of rain fell in some areas, saturating the soil and overwhelming the city’s drainage systems.

The deluge was a key trigger, but it was only part of the story. Beneath the city’s streets, a more insidious problem had been brewing for years: a network of aging, leaking sewer pipes.

Guatemala City sits on a foundation of volcanic pumice, a lightweight, porous rock formed from volcanic foam during ancient eruptions.

Unlike solid bedrock, pumice is highly permeable and prone to erosion when exposed to water.

Over time, water from leaking sewer pipes seeped into the ground, slowly eroding the pumice and creating underground cavities.

These voids grew larger, unnoticed, until the ground above could no longer bear the weight.

The torrential rains from Agatha accelerated this process, widening the cavities and triggering the collapse.

Geologists describe this type of event as a “piping pseudokarst” feature, distinct from traditional sinkholes that form in limestone-rich karst terrain.

In Guatemala City, the absence of limestone and the presence of loose volcanic deposits made the ground particularly vulnerable.

The role of human negligence cannot be overlooked. For years, residents in Zona 2 and nearby Zona 6 had reported rumblings, fissures, and sinking terrain—warning signs that went largely unheeded.

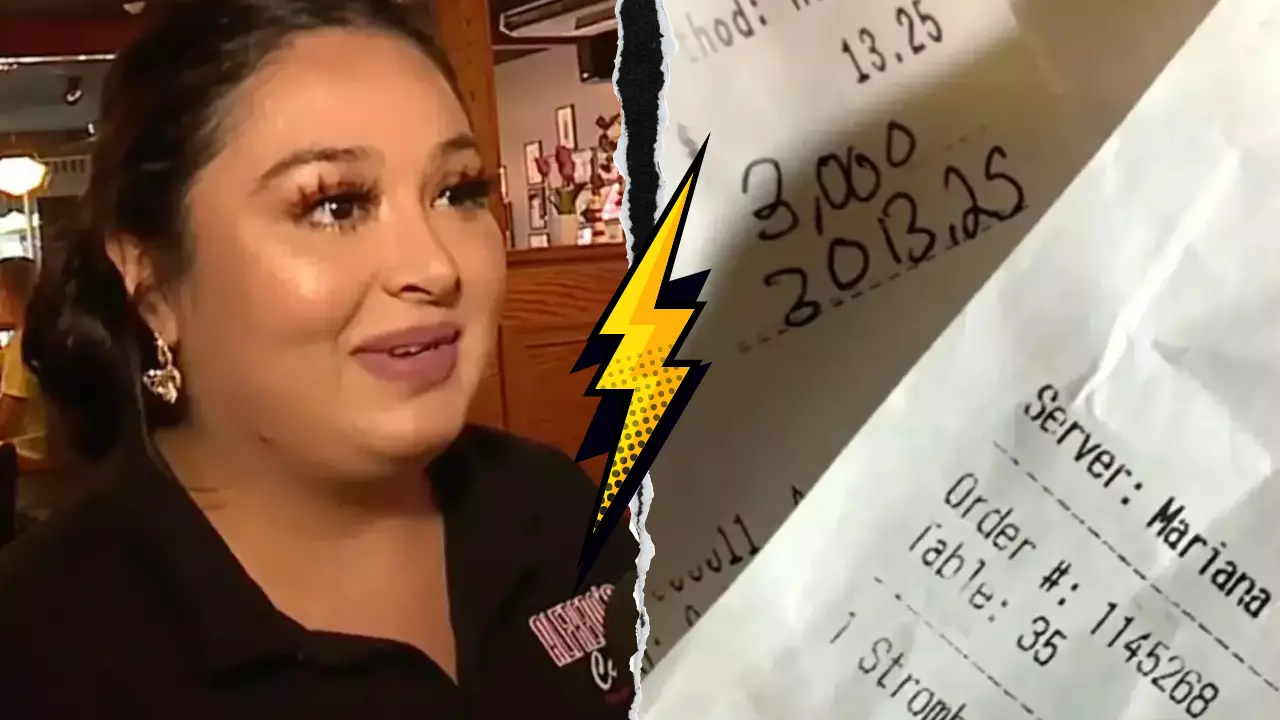

Since 2005, Guatemala City’s human rights ombudsman, Sergio Morales, had documented these complaints, yet the city’s aging sewer system received inadequate maintenance.

Zoning regulations and building codes allowed construction on unstable ground without sufficient safeguards, exacerbating the risk.

Some experts, including Augusto Lopez Rincon, president of a local neighborhood association, suggested that heavy traffic from commercial trucks may have further stressed the ground, contributing to the instability.

The collapse itself was nothing short of catastrophic. On that fateful Sunday, the ground gave way with a deafening roar, swallowing the factory and part of a street intersection.

Aerial photographs revealed a strikingly cylindrical crater, so deep that its bottom was barely visible.

Miraculously, only one death was reported, possibly a security guard, though conflicting reports leave the exact toll uncertain.

The event left residents in a state of shock and fear, unsure whether their homes were safe.

Many faced the agonizing decision of whether to stay or evacuate, as the ground beneath them no longer felt trustworthy.

This was not Guatemala City’s first encounter with such a disaster. In February 2007, another sinkhole opened in Zona 6, just a few kilometers away, measuring 100 meters deep and claiming three lives.

That incident, too, was linked to leaking sewer pipes and heavy rainfall, which eroded the same volcanic ash and pumice deposits.

The 2007 sinkhole swallowed a dozen homes and forced the evacuation of over a thousand people, prompting a $2.7 million effort to redirect sewer pipes and fill the crater with soil cement, known locally as lodocreto.

The similarities between the two events raised alarm bells about the city’s vulnerability and the need for systemic change.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Date | 30 May 2010 |

| Location | Guatemala City, Zona 2 |

| Size | Diameter: 20 m (65 feet), Depth: 90 m (300 feet) |

| Cause | Combination of Tropical Storm Agatha, Pacaya Volcano eruption, and leaking sewer pipes |

| Impact | Swallowed a three-story factory, 1 death (unconfirmed) |

| Similar Incident | 2007 sinkhole in Zona 6, 100 m (330 feet) deep, 3 deaths |

In the wake of the 2010 sinkhole, Guatemala City faced intense scrutiny over its infrastructure.

The government declared a state of emergency due to the broader devastation caused by Tropical Storm Agatha, which killed over 175 people across Central America and left schools closed until at least June 4.

Municipal authorities moved quickly to rebuild damaged sewer collectors and initiated inspections of the underground infrastructure.

These inspections revealed troubling findings: groundwater infiltration, caverns, and cracks in the concrete, all of which pointed to ongoing risks.

Geologists, including Sam Bonis from Dartmouth College, emphasized that the city’s sewer system needed regular government inspections to prevent future collapses.

Efforts to mitigate the risk have included both immediate and long-term measures.

After the 2007 sinkhole, the city improved its wastewater and runoff management, but the 2010 event showed that these efforts were insufficient.

Post-2010, authorities conducted geophysical surveys to map underground cavities and identify high-risk areas.

These surveys informed plans to reinforce weak spots and divert water flow away from vulnerable zones.

Upgrades to wastewater treatment plants also aimed to reduce ground infiltration, a key factor in cavity formation.

Two main methods were proposed to fill the 2010 sinkhole. The first was to use soil cement, a mixture of cement, limestone, and water, which had been used successfully in 2007.

The second was a graded-filter technique, involving layers of boulders, smaller rocks, and gravel to stabilize the ground while allowing water to seep through.

Both approaches aimed to restore stability, but filling such a massive crater in an urban area posed logistical challenges, especially in Guatemala City’s densely populated slums, where transportation and access are limited.

Despite these efforts, experts warn that Guatemala City remains a geological time bomb.

The city’s foundation of volcanic deposits makes it inherently prone to sinkholes, and climate change is likely to exacerbate the problem by bringing more extreme weather events.

Regular maintenance of the sewer system is critical, yet municipal authorities have faced criticism for neglecting this responsibility.

Urban planning must also evolve, with stricter building codes to prohibit construction in high-risk areas or require specialized foundations to withstand subsidence.

Public awareness campaigns could further help by encouraging residents to report early signs of ground instability, such as cracks or unusual noises.

As the city continues to grow, it must invest in robust infrastructure, rigorous maintenance, and sustainable urban planning to prevent history from repeating itself.

The earth beneath Guatemala City may appear solid, but as the events of 2010 revealed, it can vanish in an instant, leaving behind a void that challenges our understanding of safety and stability.

What lies beneath other cities, waiting to give way?