Beirut’s Catastrophic Explosion: 2,750 tons chemical blast wounds 7,000, leaves 300,000 homeless

- Blast equivalent to 1.1 kilotons of TNT rocks Lebanon capital.

- Over 300,000 displaced amid $15 billion in damages.

- Multiple warnings ignored for six years by officials.

One of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history unleashed a seismic shock equivalent to a 3.3 magnitude earthquake, detectable as far as Cyprus, 240 kilometers away.

The afternoon of August 4, 2020, began with routine activity at Beirut’s bustling port.

Warehouse 12, a nondescript structure near the waterfront, housed a deadly secret that would soon shatter the city.

At approximately 5:45 p.m. local time, smoke billowed from the building, drawing the attention of nearby workers and passersby.

Firefighters rushed to the scene, unaware of the peril lurking inside. What started as a fire quickly escalated into chaos.

Eyewitnesses described pops resembling fireworks, followed by a smaller blast that tore through the warehouse.

Then, 33 seconds later, the main detonation erupted with unimaginable force, sending a mushroom cloud skyward and a shockwave ripping across neighborhoods.

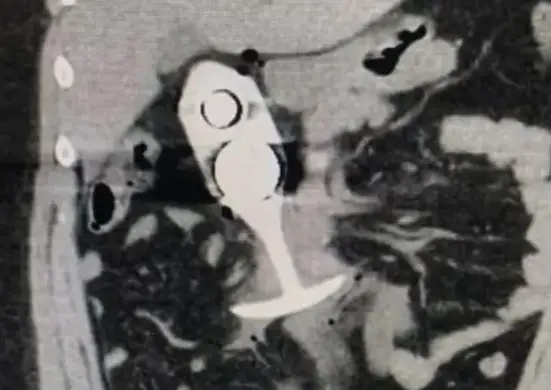

The source of this ammonium nitrate blast traced back to 2013, when the Moldovan-flagged cargo ship MV Rhosus docked in Beirut due to mechanical issues.

Bound for Mozambique, the vessel carried 2,750 tonnes of high-grade ammonium nitrate, a chemical fertilizer with explosive potential when mishandled.

Port authorities impounded the ship over unpaid fees and safety violations, offloading the cargo into Warehouse 12 in 2014.

There it sat, year after year, amid fireworks, tires, and other flammable materials, in violation of basic storage protocols.

Why did no one act? Documents later revealed a tangled web of bureaucracy and indifference that allowed this Lebanon port disaster to brew.

As the fireball expanded, the explosion’s yield reached an estimated 1.1 kilotons of TNT equivalent, based on seismic and infrasound data analyzed from global monitoring stations.

This power dwarfed many conventional blasts, carving a crater 124 meters wide and 43 meters deep at the epicenter.

Debris flew outward at supersonic speeds, pulverizing concrete and glass in a radius exceeding 10 kilometers.

The port’s grain silos, vital for Lebanon’s food supply, absorbed much of the initial force but partially collapsed, spilling 15,000 tonnes of wheat into the sea and worsening an already dire economic crisis.

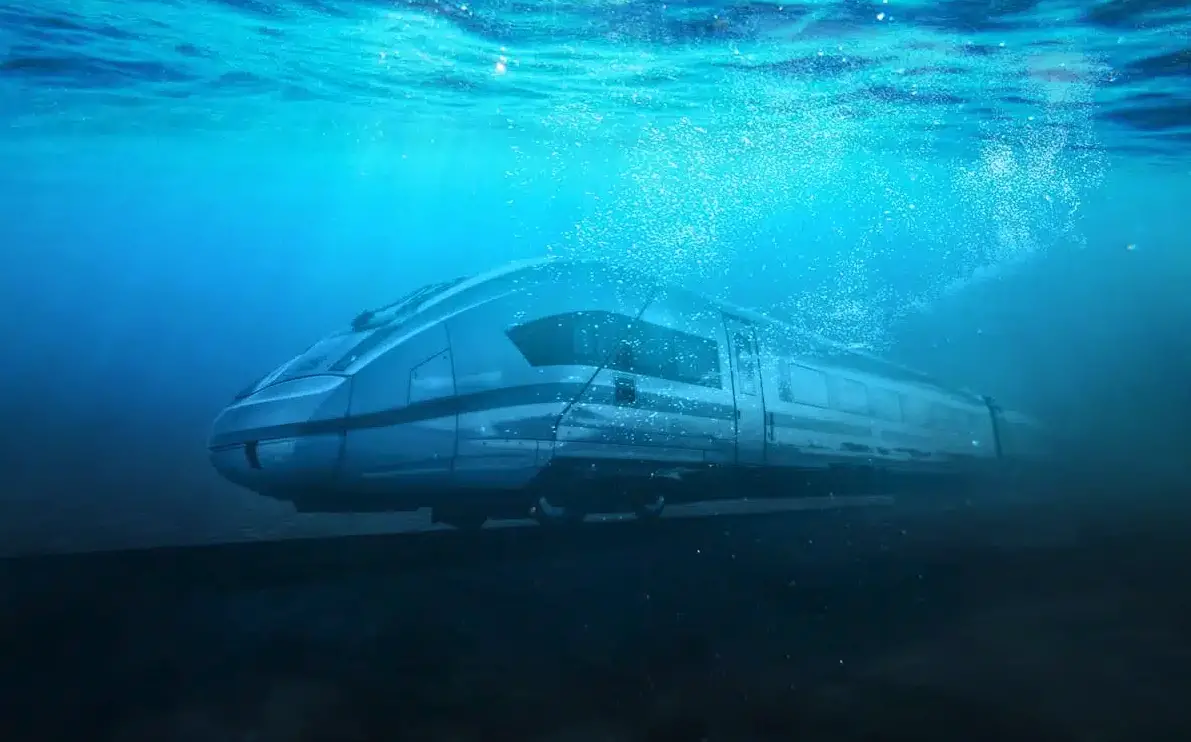

Ships moored nearby fared no better: the cruise liner Orient Queen capsized, claiming two crew lives, while others like the Amadeo II sustained hull breaches.

In the immediate aftermath, emergency responders navigated a landscape of twisted metal and rubble.

The death toll climbed steadily in the days following, reaching 218 confirmed fatalities by official counts, including Lebanese citizens, Syrian refugees, and nationals from 22 countries such as Egypt, Bangladesh, and the Philippines.

Among the lost were nine firefighters and a paramedic from Platoon 5, who perished while battling the initial blaze.

Injuries surpassed 7,000, with many suffering severe trauma: amputations, blindness from flying shards, and long-term disabilities affecting at least 150 people.

Hospitals, already strained by the COVID-19 pandemic, overflowed; three facilities near the port were destroyed, forcing medics to treat victims in parking lots under generator lights.

The human cost extended beyond physical wounds. Nearly 300,000 residents found themselves homeless overnight as the shockwave damaged 77,000 apartments and shattered windows in half the city.

Cultural landmarks bore the brunt too: the historic Sursock Palace, a 19th-century architectural gem, cracked irreparably, while the Sursock Museum’s stained-glass windows lay in ruins.

Schools numbering 160 closed indefinitely, disrupting education for 85,000 students.

Economic fallout compounded the misery, with total damages pegged at $15 billion and insured losses around $3 billion.

Businesses in the vibrant Mar Mikhael district, known for its cafes and galleries, faced bankruptcy as reconstruction costs soared.

| Metric | Figure |

|---|---|

| Deaths | 218 |

| Injuries | Over 7,000 |

| Displaced Persons | 300,000 |

| Total Damages | $15 billion |

| Material Damages | $3.8–4.6 billion |

| Insured Losses | $3 billion |

| Explosion Yield (TNT Equivalent) | 1.1 kilotons |

| Crater Dimensions | 124m diameter, 43m depth |

| Grain Lost | 15,000 tonnes |

| Affected Schools | 160 |

| Students Impacted | 85,000 |

| Hospitals Destroyed | 3 |

| Ammonium Nitrate Stored | 2,750 tonnes |

| Buildings Damaged | 77,000 apartments |

| International Aid Pledged | 253 million euros (August 2020) |

This table underscores the scale of the catastrophe, yet numbers alone fail to capture the lingering questions.

How could such a hazard persist in a densely populated area? Investigations peeled back layers of negligence that pointed to systemic failures at the highest levels.

As early as February 2014, customs official Colonel Joseph Skaf flagged the ammonium nitrate’s explosive risks in a memo, urging its removal from the port.

Similar alerts followed: in October 2014, May 2015, February 2016, and March 2018, Nehme Brax of the customs manifest department warned of ignition dangers and improper storage, recommending transfer to the Lebanese Army or re-export.

None prompted action. By 2015, the army itself knew of the material but dismissed responsibility, despite its mandate over munitions.

State Security’s Major Joseph Naddaf issued a dire report on May 28, 2020, predicting catastrophic outcomes if ignited, yet it reached President Michel Aoun and Prime Minister Hassan Diab only on July 20—too late to avert disaster.

Higher echelons bore direct knowledge. The Higher Defense Council, chaired by Aoun, omitted the issue from agendas despite briefings.

Former ministers like Ali Hassan Khalil, Ghazi Zeaiter, and Youssef Fenianos received updates but prioritized procedural delays over safety.

Customs chiefs Shafik Merhi and Badri Daher attempted flawed sales or re-exports, ignoring judicial orders for secure handling.

Even General Security Director Abbas Ibrahim, informed since 2014, claimed no jurisdiction.

This pattern of evasion, rooted in Lebanon’s sectarian power-sharing system, fostered corruption and opacity at the port, as later World Bank assessments confirmed.

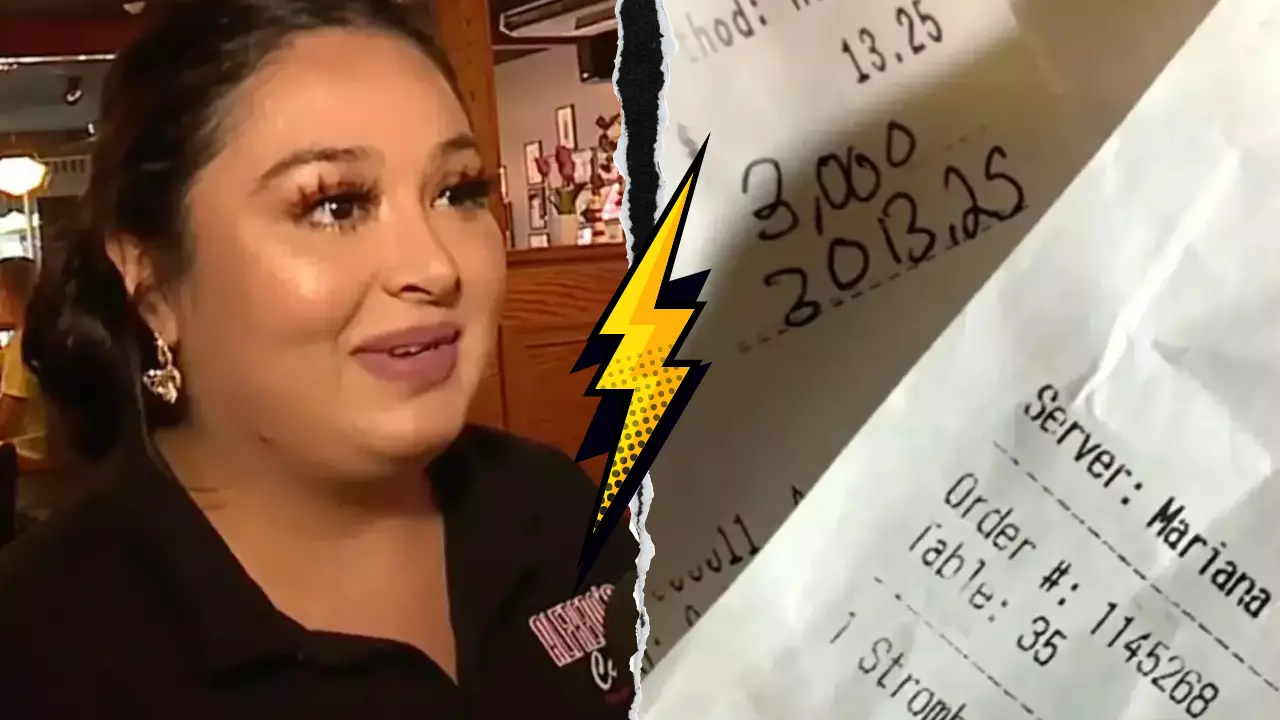

The probe, launched August 13, 2020, under Judge Fadi Sawan, charged 37 individuals, mostly mid-level figures like port manager Hassan Koraytem and customs official Mohammad al-Mawla.

Sawan targeted top officials in December 2020, accusing Diab and three ex-ministers of criminal negligence leading to homicide with probable intent.

Political backlash ensued: Sawan was ousted in February 2021 after complaints from charged politicians.

His successor, Judge Tarek Bitar, persisted, seeking to lift parliamentary immunities and charging ex-army commander Jean Kahwaji in July 2021.

Yet obstacles mounted—refusals from Interior Minister Mohammad Fehmi and parliament stalled progress, sparking protests and clashes.

By January 2025, the investigation revived, with Bitar charging ten more people, including security and military personnel.

An indictment loomed for August 4, 2025, the blast’s fifth anniversary, promising potential breakthroughs.

Families of victims, however, demanded international oversight, citing eroded trust in domestic courts amid ongoing impunity.

The FBI assisted early on, while groups like Forensic Architecture used 3D models to reconstruct Hangar 12, exposing storage lapses.

International aid poured in swiftly, with France hosting a summit on August 9, 2020, raising 253 million euros for direct relief.

The United Nations appealed for $565 million, dispatching teams alongside contributions from Qatar, Egypt, and the United States.

Rescue operations uncovered survivors days later, but long-term effects lingered: mental health crises surged, with studies linking the trauma to widespread PTSD among the population.

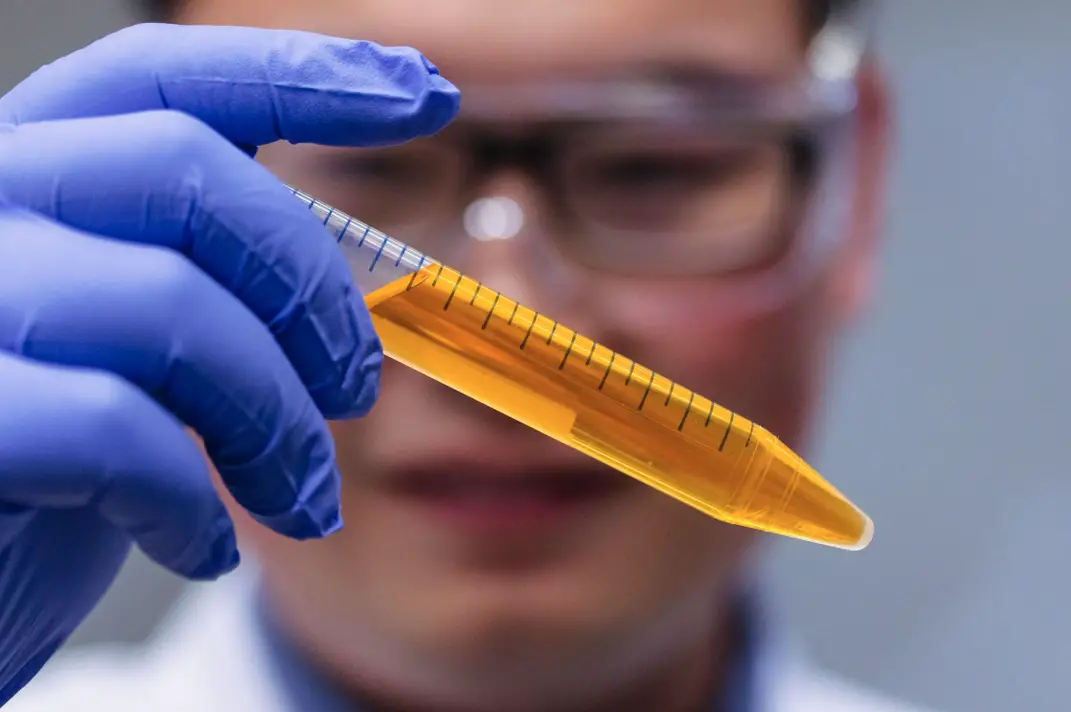

Environmental concerns emerged too, as chemical residues contaminated air and water, prompting monitoring by local scientists.

Political reverberations reshaped Lebanon. Prime Minister Diab’s cabinet resigned on August 10, 2020, amid mass demonstrations decrying corruption.

The explosion accelerated the country’s financial meltdown, with the Lebanese pound plummeting and inflation spiking to 150 percent by year’s end.

Grain shortages threatened famine in a nation importing 80 percent of its food.

Cultural recovery efforts, led by UNESCO, aimed to restore sites like the National Museum, but funding gaps persisted.

VIDEO: What happened in deadly Beirut explosion

Five years on, silos at the port still smolder intermittently, a grim reminder of unresolved accountability.

What new revelations might bring, and will it finally pierce the veil of immunity shielding those who knew?