Sending kids through the mail: The bizarre U.S. postal service practice of 1913

A New Era for the Postal Service

On January 1, 1913, the U.S. Postal Service launched Parcel Post. This service allowed Americans to send packages weighing up to 50 pounds.

Before this, packages were capped at four pounds. The change revolutionized commerce and communication.

Rural families gained access to goods like never before. But the vague regulations led to some surprising uses. Among them: mailing children.

The First Mailed Child: James Beagle

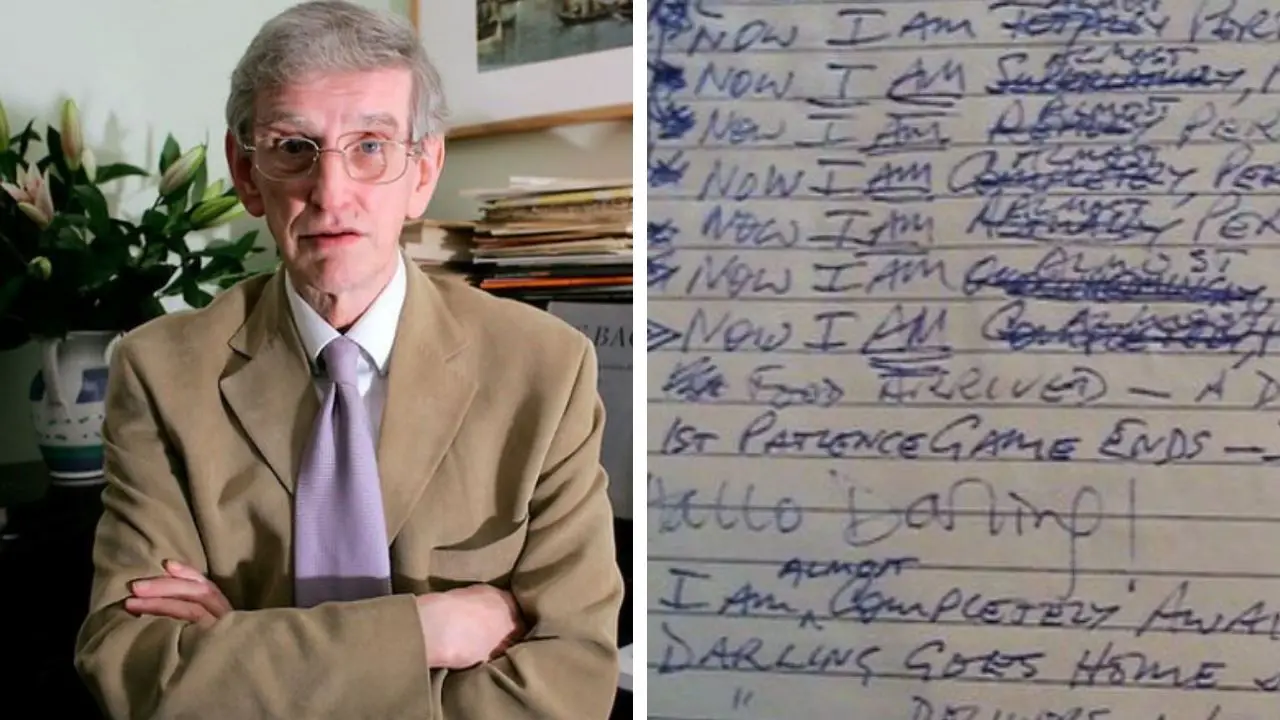

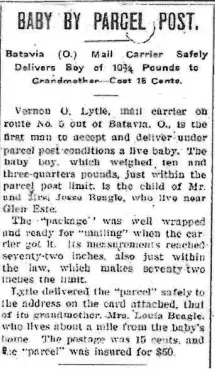

Just weeks after Parcel Post began, Jesse and Mathilda Beagle of Glen Este, Ohio, made history.

They mailed their 8-month-old son, James, to his grandmother in Batavia, Ohio. The distance was only a mile.

James weighed just under the 11-pound limit for parcels. His parents paid 15 cents for postage.

They also insured him for $50, showing caution. Rural Carrier Vernon Lytle picked up James.

He carried the baby in his mail wagon to his grandmother’s home. The story hit newspapers, sparking amusement and curiosity nationwide.

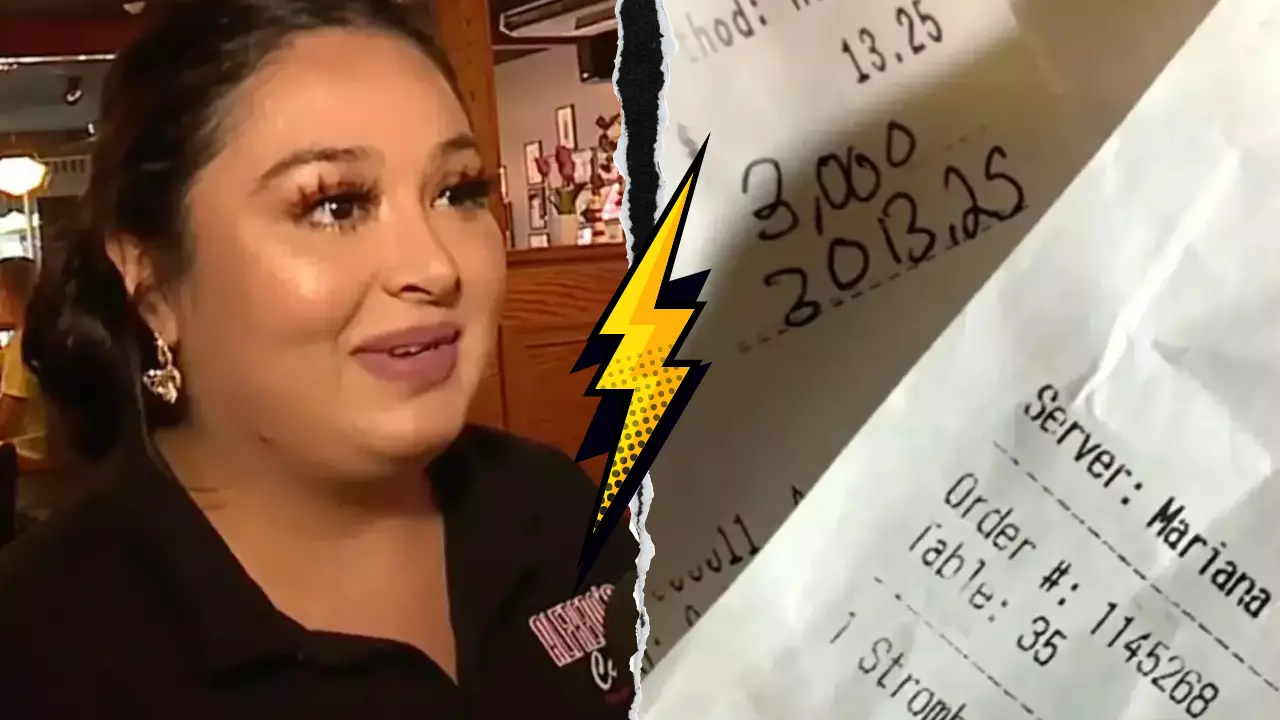

The Most Famous Case: May Pierstorff

The most well-known case involved 4-year-old Charlotte May Pierstorff. On February 19, 1914, her parents in Grangeville, Idaho, sent her to her grandparents in Lewiston, 73 miles away.

They pinned 53 cents in stamps to her coat. May was handed to a railway mail clerk, her mother’s cousin.

She traveled in a Railway Mail car, where mail was sorted on passenger trains. May’s journey was safe and uneventful. Her story later inspired a children’s book, Mailing May.

Other Notable Instances

Other children were mailed, though cases were rare. In 1915, 6-year-old Edna Neff traveled from Pensacola, Florida, to Christiansburg, Virginia—720 miles—for just 15 cents.

Another case involved Maud Smith, mailed 40 miles in Kentucky in August 1915. This was the last known instance, investigated by Superintendent John Clark. These cases show how loosely rules were interpreted early on.

| Child Name | Details |

|---|---|

| James Beagle | 1913, 8 months old, 1 mile, 15 cents, mailed to grandmother in Ohio, insured for $50 |

| May Pierstorff | 1914, 4 years old, 73 miles, 53 cents, sent via Railway Mail, accompanied by relative |

| Edna Neff | 1915, 6 years old, 720 miles, 15 cents, mailed from Florida to Virginia |

| Maud Smith | 1915, age unknown, 40 miles, cost unknown, last known case, investigated in Kentucky |

Public and Media Reaction

The media jumped on these stories. Outlets like the Washington Post, New York Times, and Los Angeles Times reported with a mix of humor and concern.

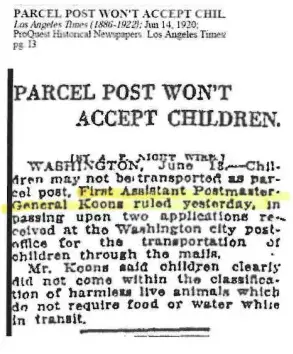

A June 14, 1913, Washington Post article noted the Postmaster General’s decree banning the practice.

Public reactions varied. Some found it funny, others alarming. In rural areas, where mail carriers were trusted, it seemed practical.

Mailing a child was often cheaper than a train ticket. For example, sending a child by Railway Mail cost less than a passenger fare.

The Role of Postal Workers

Postal workers were central to these incidents. In rural communities, carriers were like family.

They delivered medicine, helped in emergencies, and even assisted with childbirth. Carrying a child along their route was an extension of this trust.

Vernon Lytle, who delivered James Beagle, knew the family well. May Pierstorff’s journey was overseen by a relative in the postal service.

Children weren’t boxed or treated like packages. They were carried or walked along the route, ensuring their safety.

Why It Happened

Parcel Post’s rules were vague in 1913. Packages up to 50 pounds were allowed, but human mail wasn’t explicitly banned.

Initially, only bees and bugs could be mailed. By 1918, day-old chicks were permitted, and in 1919, some “harmless live animals” were added.

Children were never included, but the ambiguity led to confusion. In rural areas, where train travel was expensive, mailing a child was a cost-effective option.

Local postmasters sometimes allowed it, depending on their interpretation of the rules.

Expert Insights

Historians provide context for this odd practice. Jenny Lynch, a U.S. Postal Service historian, told Smithsonian Magazine, “It got some headlines when it happened, probably because it was so cute.”

Nancy Pope, former head curator at the National Postal Museum, described the early Parcel Post years as chaotic. “The first few years—it was a bit of a mess,” she said.

“Different towns interpreted the regulations differently.” These insights explain why the practice, though rare, occurred.

The Ban and Its Aftermath

The practice ended quickly. In 1914, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson banned mailing humans after cases like May Pierstorff’s gained attention.

By June 1920, First Assistant Postmaster General John C. Koons rejected requests to mail children, clarifying they weren’t “harmless live animals.”

No further cases were reported after 1915. The ban closed this brief, bizarre chapter.

Cultural Legacy

The story of mailed children lives on in American folklore. Mailing May brings the tale to young readers.

It’s also a case study in how new services can lead to unexpected uses. The practice reflects the trust rural communities had in their postal workers.

It also shows the need for clear regulations. Today, it’s a quirky reminder of a time when the postal service was still finding its footing.

For a brief period, the U.S. Postal Service delivered more than letters and packages—it delivered children.

This strange practice, born of vague rules and rural trust, lasted only a few years. By 1914, it was banned, and by 1920, fully clarified.

The story remains a fascinating glimpse into early 20th-century America, where innovation sometimes led to the absurd.