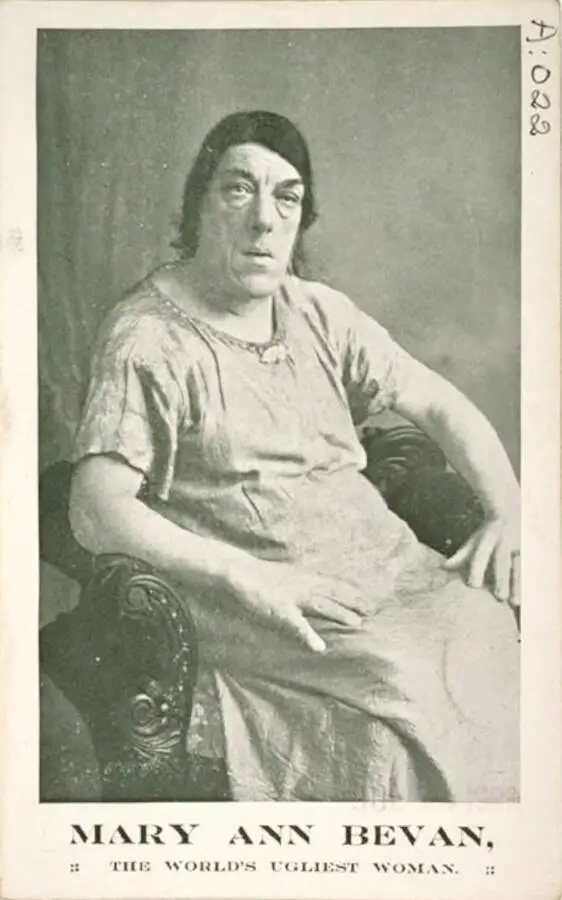

Mary Ann Bevan: The Tragic Story of the “Ugliest Woman in the World”

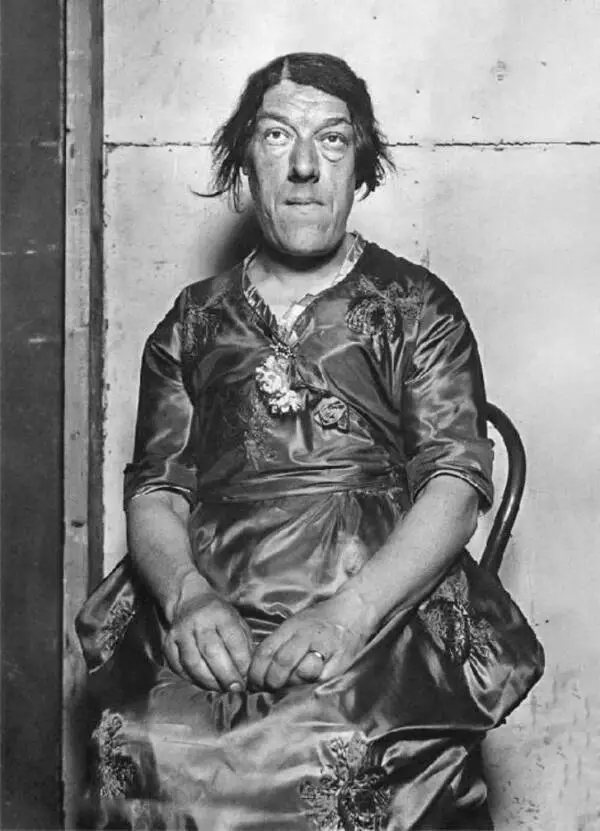

- Mary Ann Bevan, a skilled nurse born in 1874, enjoyed a normal life until acromegaly symptoms ravaged her appearance starting at age 32.

- Widowed in 1914 with four young children, she faced unemployment and poverty due to her distorted facial features and enlarged extremities.

- Joining circus sideshows in 1920, Bevan endured public ridicule but earned a fortune to secure her family’s future, showcasing extraordinary maternal resilience.

In the bustling streets of Victorian-era London, where gas lamps flickered against the fog and working-class families scraped by on meager wages, Mary Ann Webster entered the world on December 20, 1874, in Plaistow, a gritty neighborhood in Newham.

As one of eight siblings in a modest household, her early years were marked by the harsh realities of industrial Britain, yet she harbored ambitions beyond her circumstances.

Training as a nurse in her twenties, she embodied the era’s emerging opportunities for women in healthcare, tending to patients with a gentle demeanor and sharp intellect that earned her respect among colleagues.

Little did she know, a silent biological betrayal lurked within her body, one that would upend her life in ways unimaginable during those promising days.

By 1902, at age 28, Mary Ann married Thomas Bevan, a florist from Kent whose steady presence offered stability amid the uncertainties of urban life.

Their union blossomed quickly, welcoming four children—two sons and two daughters—between 1905 and 1910.

Family photographs from this period capture a radiant woman with soft features, cradling her infants in modest but loving surroundings.

However, around 1906, subtle changes began to emerge. Headaches plagued her relentlessly, accompanied by muscle aches and a peculiar swelling in her hands and feet.

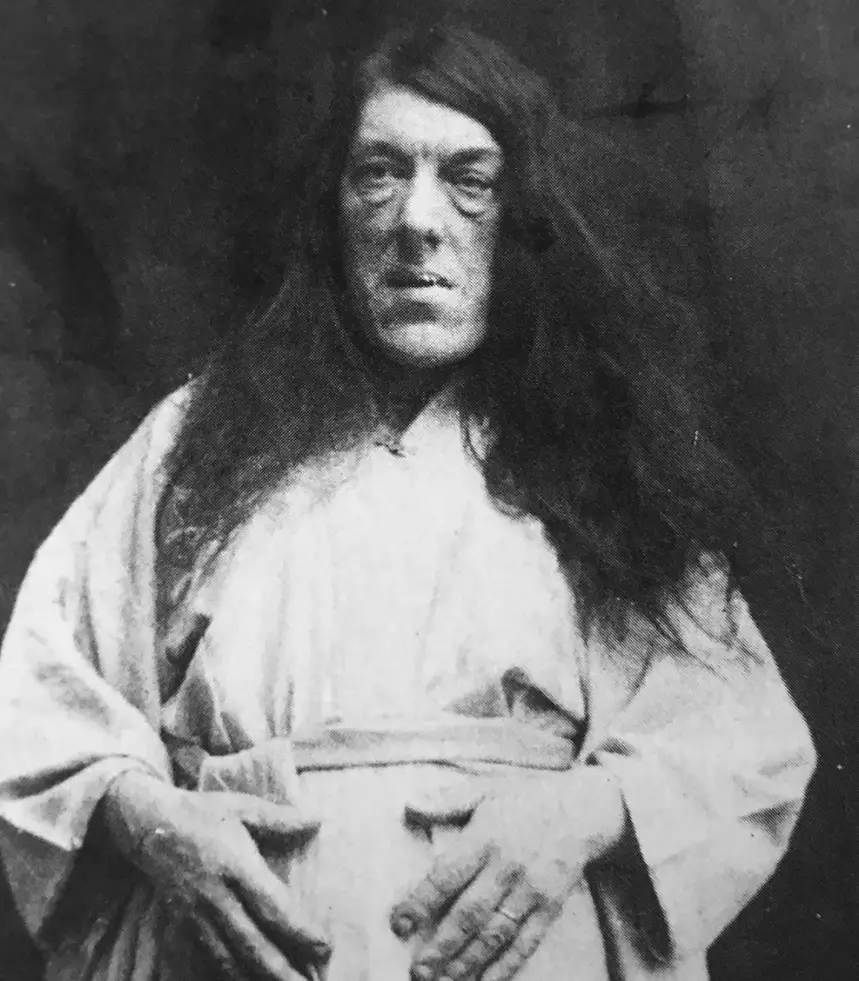

Her fingers thickened, making delicate nursing tasks increasingly difficult, while her facial bones shifted—her brow protruding, jaw extending, and nose broadening in a grotesque distortion that baffled local doctors.

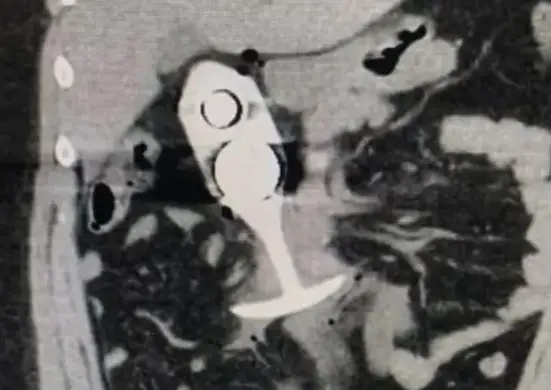

This was acromegaly, a rare hormonal disorder triggered by a benign tumor on the pituitary gland, causing excessive growth hormone production after puberty’s end.

Unlike gigantism, which strikes children and leads to extreme height, acromegaly in adults manifests through gradual enlargement of soft tissues and bones, particularly in the face, hands, and feet.

Prevalence rates hover between 40 and 70 cases per million people worldwide, with symptoms often dismissed initially as aging or fatigue.

In Mary Ann’s case, the condition brought not just physical alterations but debilitating side effects: joint pain that made walking arduous, vision impairment from compressed optic nerves, and cardiovascular strain that shortened life expectancy without intervention.

In the early 20th century, diagnostic tools were rudimentary—no MRI scans or hormone assays existed—and treatments like surgery or radiation were experimental and risky, often unavailable to someone of her social standing.

As her appearance evolved, whispers turned to stares in the hospital corridors where she worked.

Patients recoiled, colleagues averted eyes, and eventually, employment slipped away.

Thomas stood by her, but tragedy struck in 1914 when he died suddenly at age 40, possibly from a stroke, leaving Mary Ann, then 39, as the sole provider for their young family.

World War I raged across Europe, inflating food prices and straining resources in London, where widows like her faced eviction and hunger.

Desperate, she took on menial jobs—laundry, sewing—but her enlarged hands, now equivalent to a man’s ring size 25, and shoe size 11 made even these labors painful and inefficient.

Bills piled up, and the children’s education hung in the balance, prompting her to scan newspapers for any opportunity, no matter how degrading.

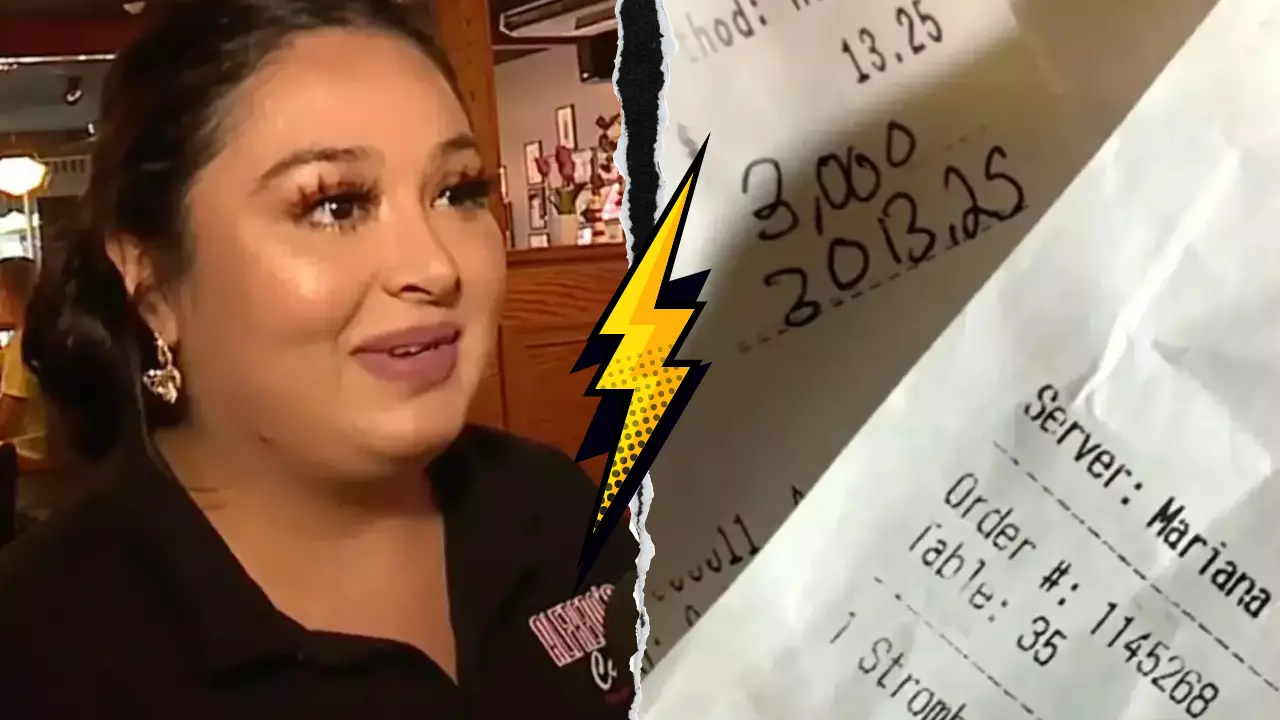

One such ad caught her eye: a contest for the “Homeliest Woman,” essentially a cruel competition seeking the most unconventional appearance, with a cash prize and potential employment in entertainment.

Against 250 entrants, Mary Ann won, her transformed visage securing the title that would define her public persona.

This victory connected her with agent Claude Bartram, who arranged gigs in British traveling fairs, where “freak shows” thrived as macabre spectacles of human oddities.

These exhibitions, popularized by P.T. Barnum in the 19th century, drew crowds eager for the thrill of the unusual—bearded ladies, conjoined twins, and now, a woman billed as the “Ugliest Woman in the World.”

But what drove her forward? The promise of steady income to shield her children from destitution, even if it meant parading her pain for pennies.

By 1920, opportunity beckoned across the Atlantic.

Sam Gumpertz, manager of Coney Island’s Dreamland amusement park in New York, hired her through Bartram, offering a contract that propelled her into America’s booming sideshow circuit.

Emigrating with hopes of anonymity and prosperity, she joined a roster of performers including Lionel the Lion-Faced Man and Zip the Pinhead, enduring long hours under glaring lights as throngs gawked and jeered.

Weighing 154 pounds on her 5-foot-7 frame, she posed for postcards sold at 12 cents each, her image immortalized in sepia tones that masked the inner turmoil.

Earnings soared—reports vary, but she amassed around £20,000 in her first two years, equivalent to over $1.6 million today—allowing her to send remittances home for boarding school fees and necessities.

Yet, the toll was immense: acromegaly’s progression brought blindness in one eye, constant migraines, and sleep apnea that left her exhausted.

| Year | Key Event | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1874 | Birth | Born Mary Ann Webster in Plaistow, London, to a working-class family of eight children. |

| 1902 | Marriage | Wed Thomas Bevan, a florist; began family life in Kent. |

| 1906 | Onset of Acromegaly | First symptoms appear: headaches, enlarged hands and feet, facial changes due to pituitary tumor. |

| 1914 | Widowhood | Husband Thomas dies suddenly, leaving her to support four children amid WWI hardships. |

| 1920 | Emigration to US | Hired by Coney Island’s Dreamland; begins full-time sideshow career. |

| 1927 | Medical Controversy | Neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing condemns media mockery of her condition. |

| 1929 | Makeover Attempt | Undergoes beauty treatments at Madison Square Garden show, but returns to performing unchanged. |

| 1933 | Death | Passes away at 59; buried in Brockley and Ladywell Cemetery, South London, per her wishes. |

Audiences at Madison Square Garden in 1929 witnessed a peculiar interlude in her routine when circus staff arranged a makeover—manicure, facial massage, and permanent wave—at a nearby salon.

Emerging with rouge and curls, she gazed in the mirror and quipped to reporters, “I guess I’ll be getting back to work,” her job secure despite the fleeting glamour.

Some spectators praised the effort, noting a softening of her features, while others mocked it as futile, comparing cosmetics on her to “lace curtains on a dreadnought’s portholes.”

Amid these spectacles, she formed unlikely bonds, like with Andrew, the giraffe keeper, who shared quiet conversations away from the crowds.

Proudly, she displayed photos of her family to select visitors, boasting of one son’s service in the British Navy, a testament to the education her sacrifices afforded.

Watch: 20 Celebrity Plastic Surgery Disasters

But the exploitation drew ire from unexpected quarters.

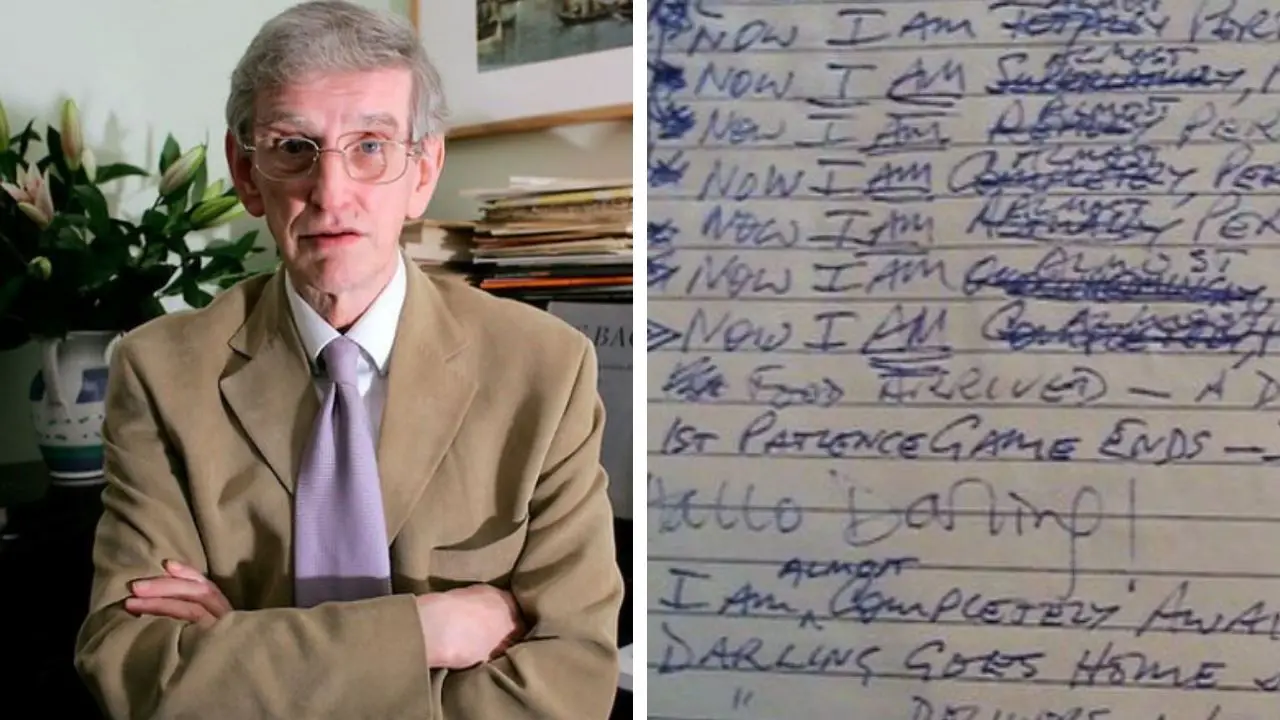

In 1927, Time magazine published a lighthearted piece on her, prompting renowned neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing to pen a scathing letter: “Being a physician, I do not like to feel that Time can be frivolous over the tragedies of disease.”

His words highlighted the ethical quagmire of freak shows, which peaked in popularity from the 1840s to 1940s, commodifying disabilities for profit while society turned a blind eye to underlying suffering.

Mary Ann’s story embodied this tension—she was no mere curiosity but a victim of circumstance, her acromegaly untreated amid risks like kidney failure and heart issues that shadowed her every performance.

As years wore on, the physical strain intensified. Vision in her remaining eye dimmed, joints screamed with each step, and the emotional weight of ridicule—children pointing, adults sneering—tested her resolve.

Yet she persisted, touring with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey, her act evolving to include personal anecdotes that humanized her beyond the billing.

What secrets did she share in those hushed moments?

Whispers of lost dreams, perhaps, or regrets unspoken, as she funneled earnings into trusts for her offspring, ensuring they escaped the poverty that ensnared her youth.

Decades later, her image resurfaced in a 2000 Hallmark greeting card series in the UK, parodying a dating show with her photo captioned as a “blind date” horror.

Dutch endocrinologist Wouter de Herder, fresh from researching her case, lodged a complaint, arguing it insulted acromegaly patients globally.

Hallmark withdrew the cards, acknowledging, “Once we found that this lady was ill, rather than simply being ugly, then the card was withdrawn immediately.”

This modern echo amplified her legacy, sparking discussions on body shaming and historical insensitivity, but what of her children’s fates—did they carry forward her untold stories, or did silence shroud the pain she bore so stoically?

In her final years at Coney Island, as crowds thinned and health faltered, Mary Ann clung to one fervent wish: to return home in death, far from the glaring spotlights that both saved and scarred her.

On December 26, 1933, she slipped away quietly at 59, her body shipped across the ocean for burial in South London’s Brockley and Ladywell Cemetery.

But as the earth covered her, questions linger— what hidden letters or diaries might reveal the depths of her inner strength, waiting to be unearthed by those who dare to look beyond the surface?