Man Has Just a Seven-Second Memory After Being Infected by a Virus

- Clive Wearing, a British musicologist, contracted herpes simplex virus in 1985, causing severe amnesia with a 7-30 second memory span.

- Brain damage from viral encephalitis destroyed his hippocampus, impairing new memory formation and erasing much of his past.

- Despite amnesia, Wearing retains musical talent and a deep emotional bond with his wife, raising questions about memory and resilience.

London – Imagine waking up every few seconds, convinced it’s the first time you’ve been conscious in years, with no recollection of the moments before.

This isn’t a scene from a sci-fi thriller but the daily reality for Clive Wearing, a once-celebrated conductor whose life was upended by a rare viral encephalitis attack.

As the world around him moves forward, Wearing remains trapped in an endless loop of neurological oblivion, raising profound questions about the fragility of human memory and the resilience of the mind.

Born on May 11, 1938, in the United Kingdom, Clive Wearing built a illustrious career in the world of classical music.

As a tenor, keyboardist, and expert in early music, he contributed significantly to the cultural landscape.

He edited the complete works of 16th-century composer Orlande de Lassus and performed as a lay clerk at Westminster Cathedral.

His talents extended to founding the Europa Singers of London in 1968, an amateur choir that gained acclaim for its performances of Baroque and contemporary pieces.

Under his direction, the group competed internationally, including at the Concorso Polifonico Internazionale in Arezzo, Italy, in 1984, and provided choruses for operas at Sadler’s Wells Theatre.

By the early 1980s, Wearing had become a key figure at BBC Radio 3, curating musical content for major events like the royal wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981, where he recreated historical sounds with period instruments.

But in March 1985, at the peak of his professional success, everything changed.

What started as flu-like symptoms—headaches, fever, and confusion—quickly escalated into a life-altering crisis.

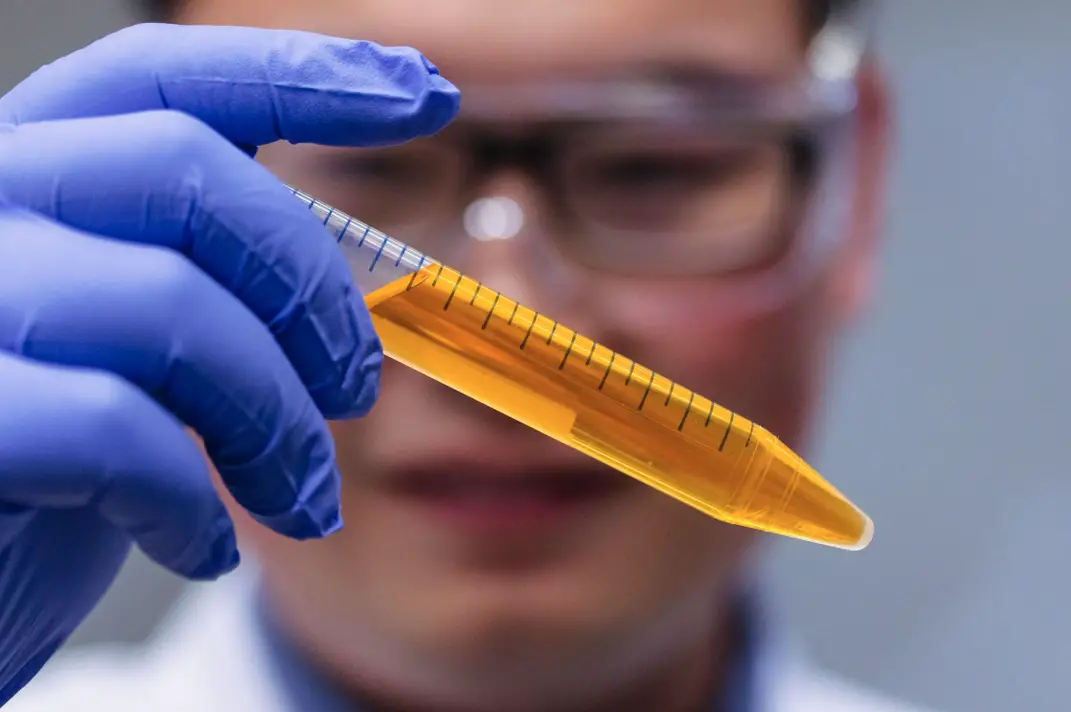

Wearing had contracted herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), a common pathogen that typically causes cold sores but in rare cases can invade the brain, triggering herpesviral encephalitis.

This aggressive inflammation targeted his central nervous system, ravaging critical structures.

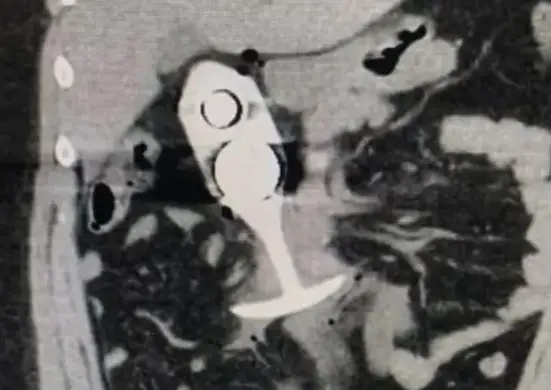

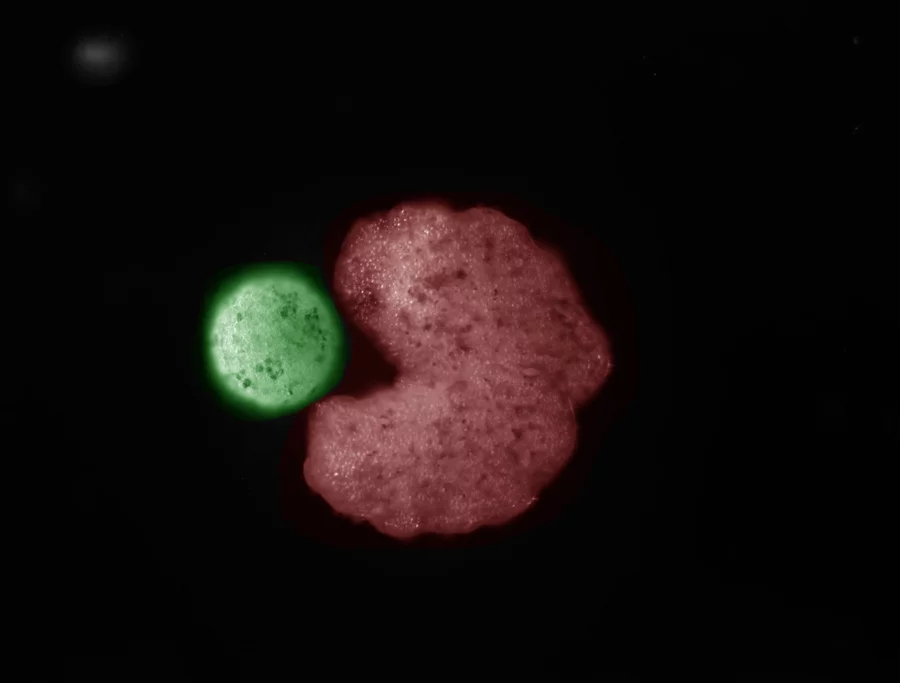

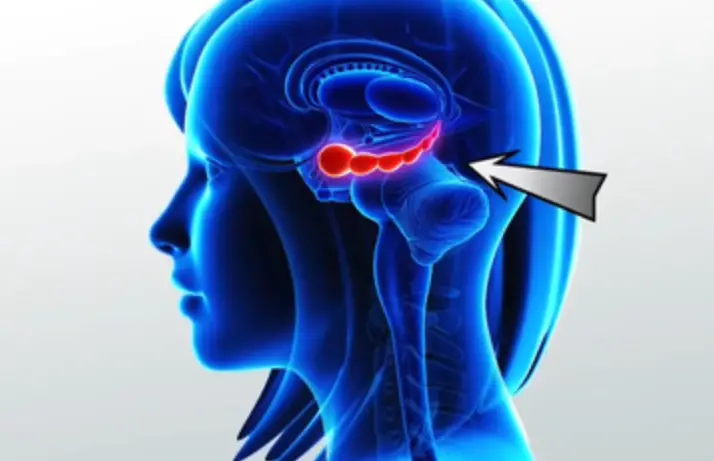

Doctors later determined that the virus had caused necrotizing damage, particularly to the hippocampus, the brain region essential for transferring experiences from short-term to long-term storage.

The aftermath was catastrophic. Wearing emerged from a coma with chronic anterograde amnesia, rendering him unable to form any new memories, combined with severe retrograde amnesia that erased vast swaths of his pre-1985 life.

He remembers fragments—like having children from a previous marriage—but not their names or faces.

Scientific assessments revealed his explicit memory for events lasts mere seconds, often cited as between 7 and 30, forcing his consciousness to reset repeatedly.

This creates a harrowing existence where every interaction feels like the first, and the passage of time is an abstract concept he can’t grasp.

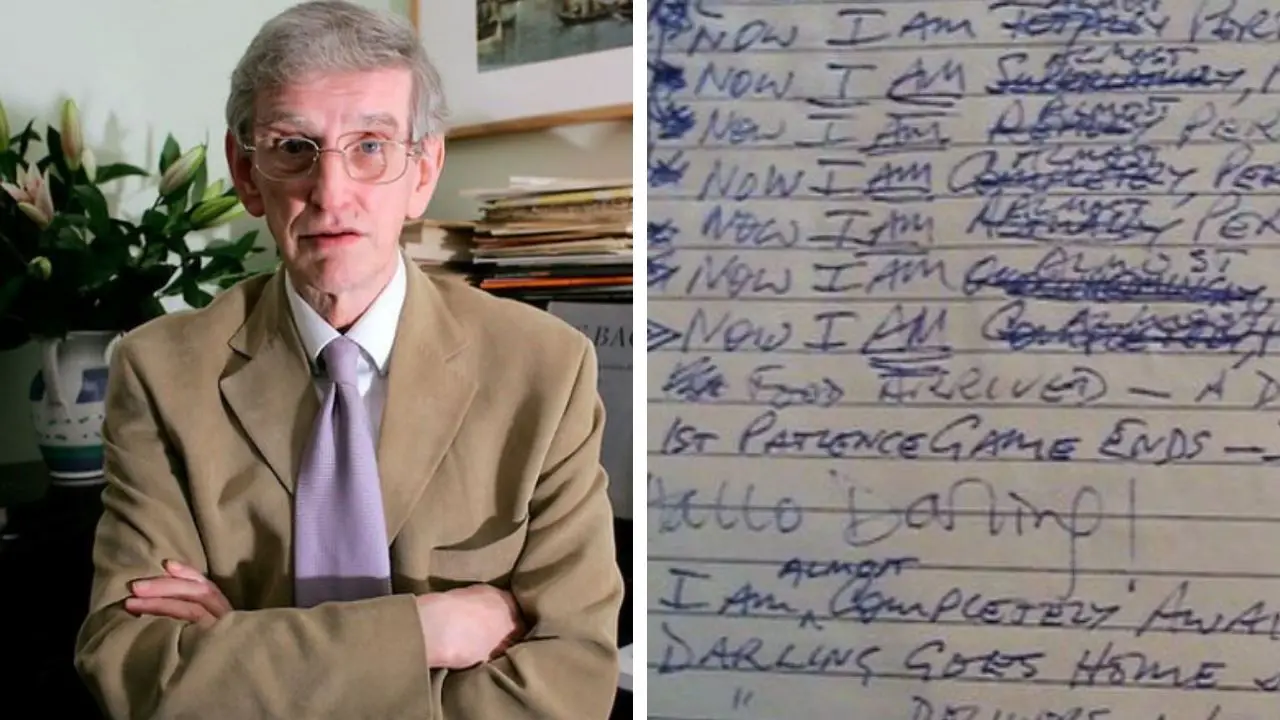

In the initial weeks, Wearing’s confusion manifested in bizarre ways.

He would hide objects, like a piece of chocolate, only to “discover” them moments later with genuine surprise, exclaiming about their novelty.

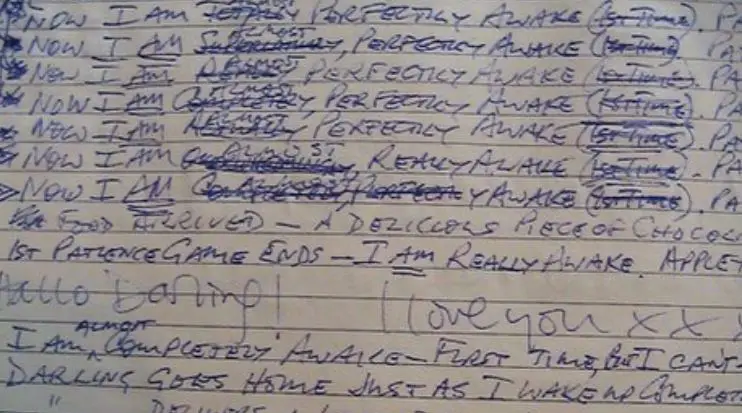

His attempts to anchor himself led to a poignant diary habit: pages filled with entries declaring his awakening, such as “8:31 AM: Now I am really, completely awake” followed by “9:06 AM: Now I am perfectly, overwhelmingly awake,” each previous note crossed out as if it belonged to someone else.

He recognizes his own handwriting but denies making the marks, underscoring the depth of his cognitive disconnect.

Medical experts describe Wearing’s case as unparalleled in its severity.

The hippocampal destruction not only halts new memory formation but also impairs his ability to sequence thoughts or anticipate outcomes.

Yet, intriguingly, certain brain functions remain untouched. Procedural memory, governed by subcortical areas like the basal ganglia and cerebellum, allows him to execute complex skills without conscious recall.

This preservation offers glimpses into how the brain compartmentalizes abilities, even amid widespread injury.

| Fact | Details |

|---|---|

| Birth Date | May 11, 1938 |

| Infection Date | March 27, 1985 |

| Cause | Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1) Encephalitis |

| Brain Areas Affected | Hippocampus, Medial Temporal Lobes, Frontal Lobes |

| Memory Span | 7-30 Seconds |

| Types of Amnesia | Anterograde and Retrograde |

| Preserved Abilities | Musical Skills, Emotional Bond with Wife |

| Documented In | “Forever Today” (2005), “Prisoner of Consciousness” (1986) |

As years passed, Wearing’s condition forced adaptations in his living arrangements.

After initial hospitalization, he spent over six years in a psychiatric unit, never recognizing his room as home.

By 1992, thanks to persistent advocacy, he moved to a specialized residence for brain-injured individuals, where routines provide some structure.

Staff note his “deads”—moments of despair when he laments being “like death” with no thoughts or dreams—yet he engages in scripted conversations on safe topics like history or science.

WATCH!

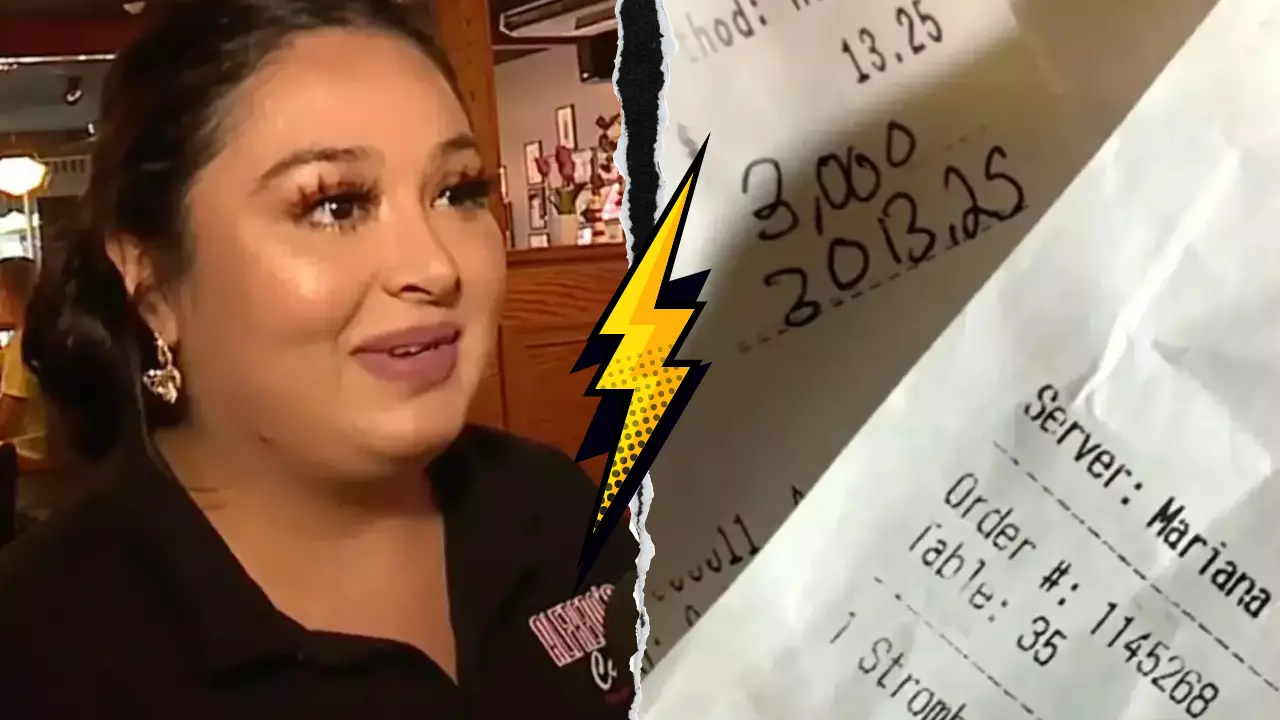

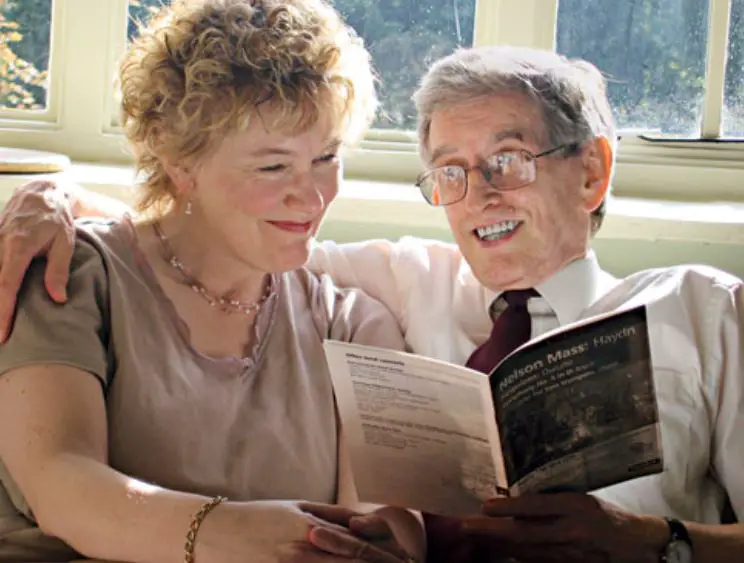

Amid this isolation, one constant shines through: his relationship with his second wife, Deborah Wearing, whom he married in 1984, just before the illness struck.

Every encounter sparks unbridled joy; he greets her with embraces as if reunited after decades, even if she’s only stepped out briefly.

“Isn’t she a wonderful woman?” he once asked during a meal, praising her affection despite forgetting the context seconds later.

Deborah, in turn, has become his anchor, documenting their journey in her memoir Forever Today: A Memoir of Love and Amnesia, which explores how love persists beyond memory’s grasp.

She describes his terror in her absence and how their bond, rooted in pre-illness emotions, transcends the amnesia barrier—perhaps tied to limbic system imprints that evade hippocampal damage.

This emotional resilience extends to his passion for music, a domain where Wearing defies his limitations.

Though he can’t recall learning pieces, he plays piano and organ with virtuosity, sight-reads scores effortlessly, and conducts choirs as if time stood still.

In one documented session, he improvised on Bach’s Prelude in E Major, infusing it with personal flair, proving that musical intelligence operates independently of episodic recall.

Neuroscientists speculate this stems from undamaged cortical and subcortical networks, offering hope for therapies in similar neurological disorders.

Decades on, Wearing’s story continues to captivate researchers studying brain injury and short-term memory loss.

In the 1980s and 1990s, his case informed understandings of how viruses like HSV-1, which affects up to 80% of adults latently, can turn deadly in immunocompromised individuals.

Annual incidences of herpes encephalitis hover around 1 in 500,000, but Wearing’s extreme outcome highlights risks of delayed treatment.

Advances in antiviral drugs, like acyclovir introduced around that era, have since improved prognoses, yet his experience underscores gaps in preventing long-term sequelae.

As of 2025, at age 87, Wearing resides in care, his condition unchanged, still greeting each day—or each second—with the same bewildered freshness.

But what if hidden neural pathways hold untapped potential for recovery, or could emerging technologies like neural implants bridge his memory voids?