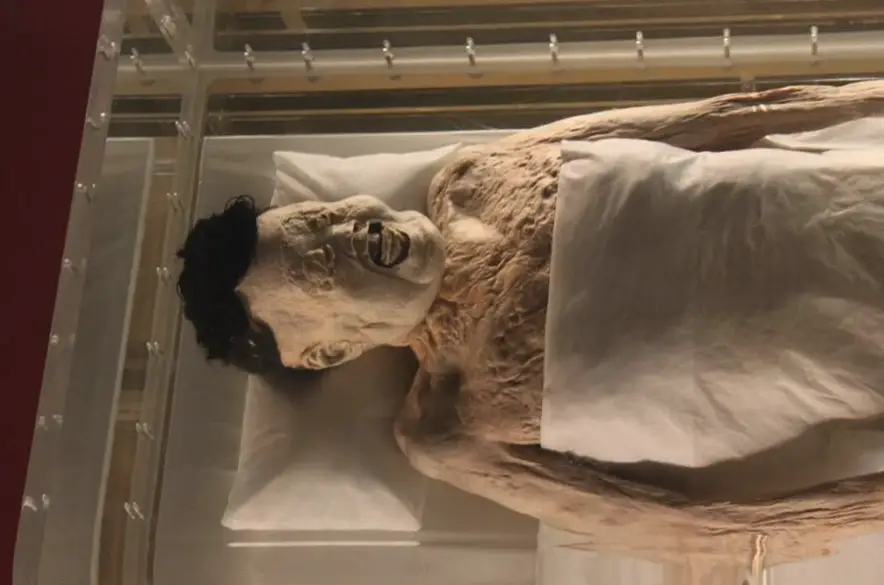

World’s Best-Preserved Mummy, 2,000-year-old Lady Dai, still has blood in her veins

- Lady Dai, a 2,000-year-old Han Dynasty noblewoman, is the world’s best-preserved mummy, with intact skin, flexible joints, and even blood in her veins.

- Her airtight tomb, filled with a strange liquid and sealed with charcoal and clay, has kept her body pristine, baffling modern scientists.

- Her tomb, packed with over 1,000 luxurious artifacts, reveals the opulent lifestyle and afterlife beliefs of Han Dynasty elites.

When we think of mummies, the first thing that usually comes to mind is ancient Egypt — the famous tombs of Pharaohs like Tutankhamun.

But did you know that the world’s best-preserved mummy isn’t from the land of the Nile? In fact, it’s not even Egyptian.

It comes from China, and her name is Lady Dai. Also known as the “Diva Mummy,” this astonishingly well-preserved body has baffled scientists and fascinated the world for decades.

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons

Discovered in 1971, at the height of the Cold War, Lady Dai’s tomb was unearthed somewhat unexpectedly.

While workers were digging an air raid shelter near the city of Changsha, they stumbled upon a relic of the past far more extraordinary than anything they might have anticipated: an enormous tomb from the Han Dynasty.

Inside, there wasn’t just one body — but a wealth of artifacts and treasures, the likes of which had never been seen before.

Among the most striking finds was the body of Xin Zhui, the wife of the ruler of the Han imperial fiefdom of Dai.

She had passed away somewhere between 178 and 145 BC, at the age of approximately 50.

Yet, what immediately captured the attention of archaeologists wasn’t the intricate jewelry or the fine fabrics adorning the tomb.

No, it was the body itself — or rather, the state of preservation that left everyone in awe.

Despite having been buried for over two millennia, Lady Dai’s skin remained moist and elastic, her joints still flexible, and her features — from the eyelashes to the fine hair in her nostrils — preserved in a way that seemed nothing short of miraculous.

A Body Like No Other

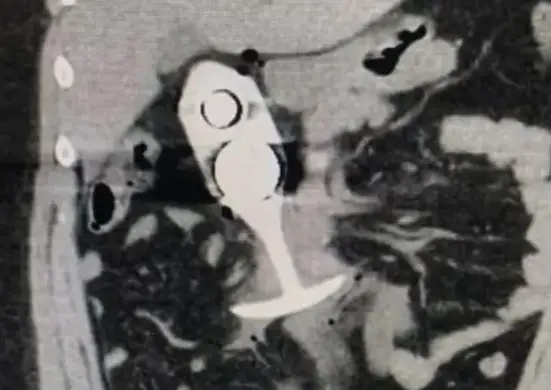

When forensic scientists conducted an autopsy on the Diva Mummy, they couldn’t believe their eyes.

It wasn’t just the condition of her skin that was remarkable. Her internal organs were still intact.

In fact, it was as if she had only recently passed away. Even her lungs had survived remarkably well, down to the tiniest of nerves — the vagus nerve, thinner than a strand of hair.

And when pathologists checked her veins, they found blood clots still present, adding to the mystery of her incredible preservation.

As the examination continued, it became clear that Lady Dai had been dealing with a number of health issues at the time of her death.

Evidence pointed to a coronary heart attack brought on by a combination of obesity, lack of exercise, and overindulgence in food.

Her diet had clearly been rich, but so had her ailments. Pathologists found traces of diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, liver disease, and even gallstones.

Perhaps one of the most telling discoveries was in Lady Dai’s digestive system.

Inside her esophagus, stomach, and intestines were 138 undigested melon seeds — a curious finding, considering melon seeds take about an hour to digest.

This led scientists to conclude that Lady Dai had likely passed away shortly after eating some melons.

But it wasn’t just the health revelations that captured the imagination of scientists. The preservation of the body itself remains a topic of much speculation.

How could her remains be so remarkably intact after more than 2,000 years? While archaeologists and pathologists have uncovered some answers, many aspects of Lady Dai’s preservation remain a mystery to this day.

The Secrets of Her Preservation

One of the most significant factors behind the preservation of Lady Dai’s body was the extraordinary conditions of her tomb.

Buried 12 meters underground, the tomb itself was sealed airtight.

The multiple layers of coffins surrounding her, along with a thick paste-like soil on the floor, helped create an incredibly stable environment.

The tomb was also surrounded by five tons of moisture-absorbing charcoal, and its top was sealed with three feet of additional clay.

No substance could enter or exit the tomb, and this lack of oxygen meant that decay-causing bacteria couldn’t thrive.

But that’s just the start of it. Lady Dai’s body was also surrounded by a highly unusual liquid — one that scientists have yet to fully identify.

The liquid was mildly acidic and contained magnesium, and the body was swaddled in 20 layers of silk.

In fact, when she was found, her body had been submerged in 80 liters of this strange substance.

Though its properties remain elusive, this liquid, combined with the airtight tomb and other factors, likely played a key role in preserving Lady Dai’s body.

Scientists have found other similarly preserved bodies in tombs scattered across a few hundred miles from Lady Dai’s resting place, but each time, the mysterious liquid was slightly different.

It’s clear that whatever process was used to preserve her, it wasn’t easily replicated.

Modern scientists, despite having far more advanced technology, still can’t quite replicate the conditions that kept Lady Dai’s body so pristine.

The Bounty of the Tomb

While the preservation of Lady Dai herself is nothing short of miraculous, the treasures found in her tomb are equally remarkable.

Archaeologists uncovered over 1,000 precious items, including silk garments, lacquer ware, and carved wooden figurines.

The figurines represented an army of servants who would tend to Lady Dai’s needs in the afterlife, a powerful symbol of the wealth and status she enjoyed during her life.

Among the most striking of these treasures were the 182 pieces of lacquer ware — items that remain just as vibrant today as they did when they were buried over two millennia ago.

The bold reds and deep blacks of the lacquer ware are so striking that they could be mistaken for items from a much more recent era.

These items were considered incredibly precious at the time and are now regarded as some of the finest examples of ancient Chinese craftsmanship.

Additionally, Lady Dai’s tomb contained a wide range of foods, many of which would have been considered luxuries in the time of her burial.

Over 30 bamboo cases and dozens of pottery containers held an assortment of grains, fruits, meats, and even exotic items like caterpillar fungus.

There were melons, pears, strawberries, pork, venison, duck, goose, fish, and more.

This opulent spread stands in stark contrast to the more modest diets of common folk during the Han Dynasty, further underscoring Lady Dai’s elite status.

Watch: 10 mummy discoveries that SCARED archaeologists

Ancient Chinese Beliefs

The opulence found within Lady Dai’s tomb reveals much about the worldview of the elite during the Han Dynasty.

They didn’t just want to live well — they expected to live forever.

This belief in eternal life is reflected in the sheer extravagance of her burial, with the extensive array of goods that were meant to accompany her into the afterlife.

In a way, the tomb of Lady Dai represents a moment frozen in time — an exquisite glimpse into a world that has long since disappeared.

The artifacts, the preserved body, and the stories hidden within the tomb all offer insights into the life of a woman who was both wealthy and powerful.

Yet, in the grand scheme of things, Lady Dai was not alone.

Her tomb offers a peek into the practices of a society that not only valued life but sought to preserve it in the most extraordinary ways.

A Mystery That Continues to Fascinate

Despite decades of study, the story of Lady Dai — and the mystery of her preservation — remains an enigma.

While modern science has made huge strides in understanding the complex conditions that allowed her body to remain intact, the exact process is still largely unknown.

Some believe it was the airtight tomb, combined with the strange liquid and other factors, that made it possible.

Others point to ancient Chinese morticians who may have possessed techniques that have since been lost to time.

Whatever the true secret is, the Lady of Dai continues to captivate visitors from all over the world.

Today, her body is housed in the Hunan Provincial Museum, where it is on display for those who wish to catch a glimpse of one of the world’s most remarkable human remains.