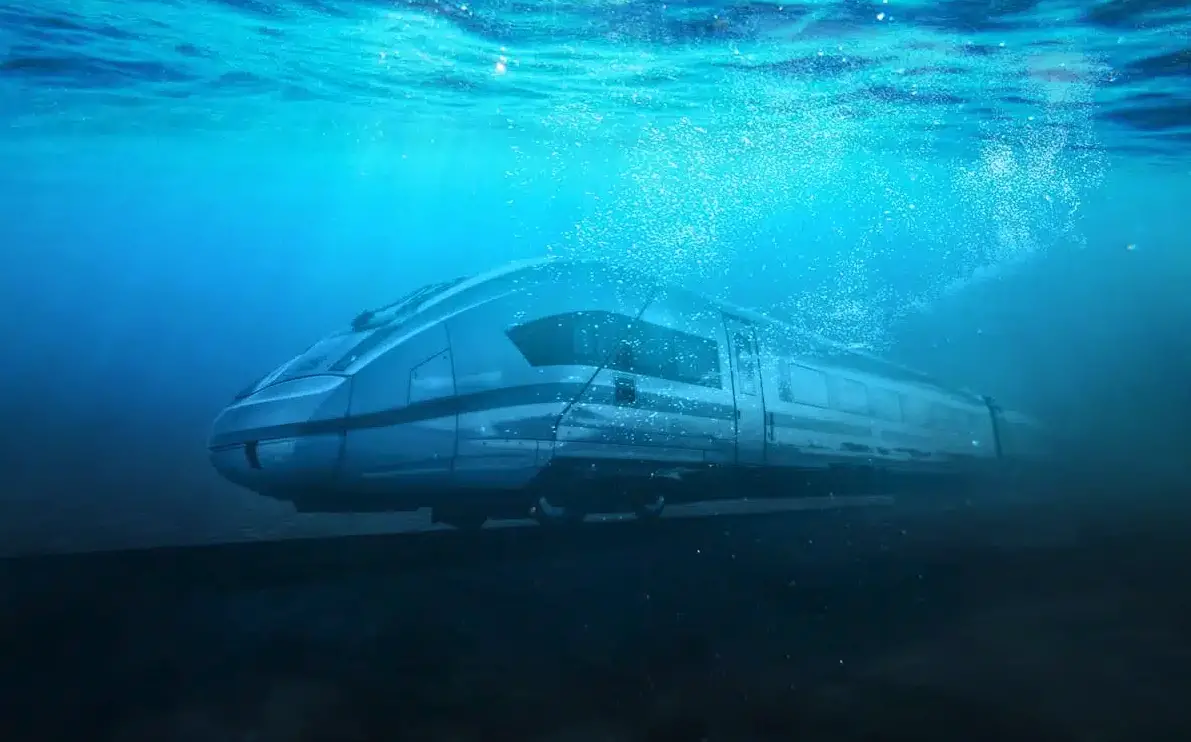

China’s $200 billion underwater train to the US: Beijing to New York in 48 hours

Imagine stepping onto a sleek, high-speed train in Beijing, settling into a comfortable seat, and arriving in New York City just two days later—without ever boarding a plane.

This isn’t a scene from a sci-fi novel but a proposal that China put forward in 2014: a $200 billion underwater rail network that would connect mainland China to the United States, traversing Siberia, Alaska, and Canada.

Known as the “China-Russia-Canada-America” line, this audacious project would span over 12,800 kilometers (8,000 miles), including a 200-kilometer (125-mile) underwater tunnel beneath the Bering Strait.

But as the years pass with little progress, the question looms: is this a groundbreaking vision of global connectivity or an unattainable fantasy?

The idea first emerged in 2014, when Chinese engineers announced they were in discussions with Russia to develop a high-speed railway that would link continents.

The project was envisioned as a cornerstone of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a massive global infrastructure program aimed at enhancing trade and connectivity across Asia, Europe, and beyond.

The proposed route would begin in northeast China, wind through Siberia, plunge beneath the icy waters of the Bering Strait, and emerge in Alaska before continuing through Canada and into the United States.

At 13,000 kilometers, it would surpass the Trans-Siberian railroad by 1,800 miles and dwarf the English Channel tunnel, which spans just 50 kilometers, in both scale and ambition.

The financial scope of the project is staggering. Estimated at $200 billion, it would consume roughly two-thirds of China’s current high-speed rail budget.

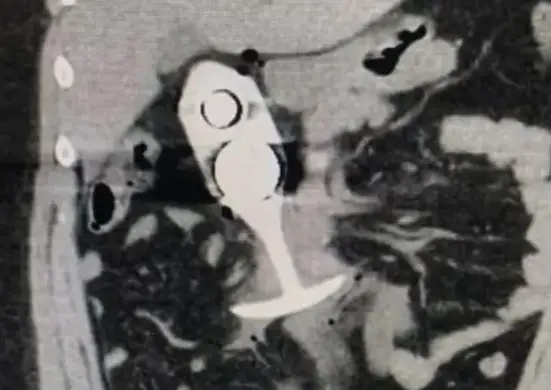

The most formidable component is the underwater tunnel under the Bering Strait, projected to cost $35 billion alone and require 12 to 15 years to construct.

This tunnel, four times longer than the Channel Tunnel, would need to be anchored to the sea floor at a depth of about 50 meters, engineered to withstand immense water pressure and prevent leaks.

Such a feat would push the boundaries of modern engineering, raising questions about its feasibility.

Yet, China’s track record suggests it’s not entirely out of reach.

The country boasts the world’s largest high-speed rail network, stretching over 23,000 miles, and operates the Shanghai Maglev, the fastest commercial electric train, reaching speeds of 431 km/h.

In 2018, China greenlit its first underwater bullet train, a 77-kilometer line connecting Ningbo to Zhoushan, including a 16.2-kilometer underwater section, set for completion in 2025.

Japan’s Seikan Tunnel, the current record-holder for the world’s longest undersea railway at 53.85 kilometers with 23.3 kilometers underwater, further proves that such technology exists.

Could China scale this expertise to conquer the Bering Strait?

Beyond engineering, the project promises significant environmental benefits. A study suggests high-speed rail could reduce environmental pollution by 7.30% compared to other transport modes.

Trains emit 80% less CO2 per kilometer than cars and only 14 grams of CO2 per passenger per kilometer, compared to 285 grams for air travel.

For a world grappling with climate change, a transcontinental rail could offer a greener alternative to carbon-heavy flights and cargo ships, potentially transforming global trade and travel.

But ambition alone doesn’t build railways, especially not ones that cross international borders.

The “China-Russia-Canada-America” line would require unprecedented cooperation among four nations: China, Russia, Canada, and the United States.

In 2014, Chinese officials, including Wang Mengshu from the Chinese Academy of Engineering, claimed discussions with Russia were underway, noting that Russia had long considered a Bering Strait connection.

However, geopolitical realities paint a less optimistic picture. Tensions between China and the US, coupled with complex relations involving Russia and Canada, make such collaboration a tall order.

Trade disputes, sanctions, and differing national priorities could derail the project before it even begins.

Skeptics have been vocal. Willis Rooney, a rail expert at GlobalData, called the project a “pipedream,” arguing that its $200 billion price tag is economically unfeasible, especially given China’s growing public debt.

The South China Morning Post echoed this sentiment, criticizing the initial budget as excessive.

Rooney also pointed out that existing air and sea routes render the railway “economically redundant.”

Why invest billions in a train when planes and ships already connect these continents efficiently?

Critics further note that ocean shipping routes and air travel are well-established, and the environmental benefits of rail might not outweigh the massive upfront costs.

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Total Cost | $200 billion |

| Total Length | 12,800 km (8,000 miles) |

| Travel Time | 2 days |

| Underwater Tunnel | 125 miles (200 km) under Bering Strait |

| Countries Involved | China, Russia, Canada, US |

| Proposed Year | 2014 |

| Current Status | On hold |

| Environmental Benefit | Reduces CO2 emissions significantly compared to air travel |

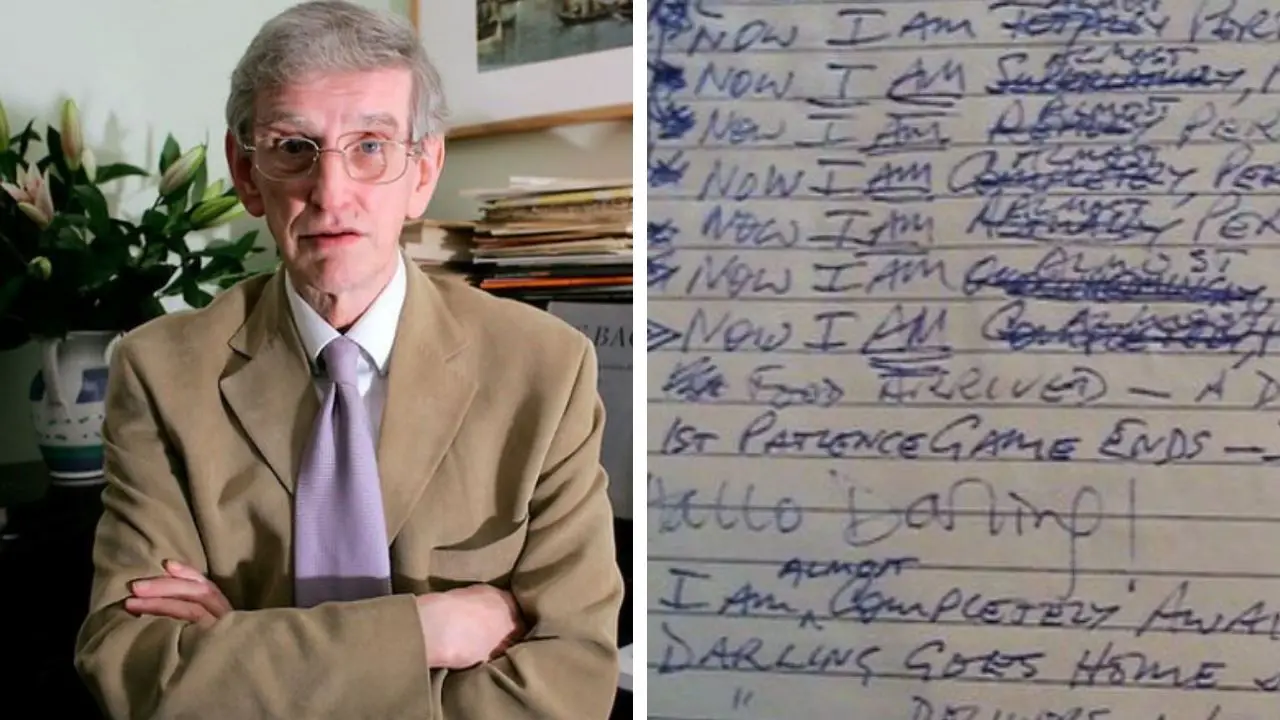

As of 2025, the project remains in limbo. Reports from 2021 indicated it was on hold, with no visible progress since its announcement.

The lack of updates suggests that the challenges—financial, technical, and political—have proven too daunting. Yet, the absence of progress doesn’t entirely dim the project’s allure.

China’s history of turning ambitious plans into reality, from the world’s longest sea bridge to its sprawling high-speed rail network, keeps the possibility alive.

The Ningbo-Zhoushan underwater railway, set to open soon, demonstrates China’s growing expertise in underwater rail technology, offering a glimpse of what might be possible.

The project’s potential to reshape global connectivity is undeniable. A two-day journey from Beijing to New York could revolutionize travel, making it faster than current sea routes and more sustainable than air travel.

It could boost trade, tourism, and economic ties among China, Russia, Canada, and the US, creating a rail network that makes the world feel smaller.

But history offers a cautionary tale: the Channel Tunnel, connecting the UK and France, was proposed in 1802 but didn’t open until 1994, delayed by nearly two centuries of political and financial hurdles.

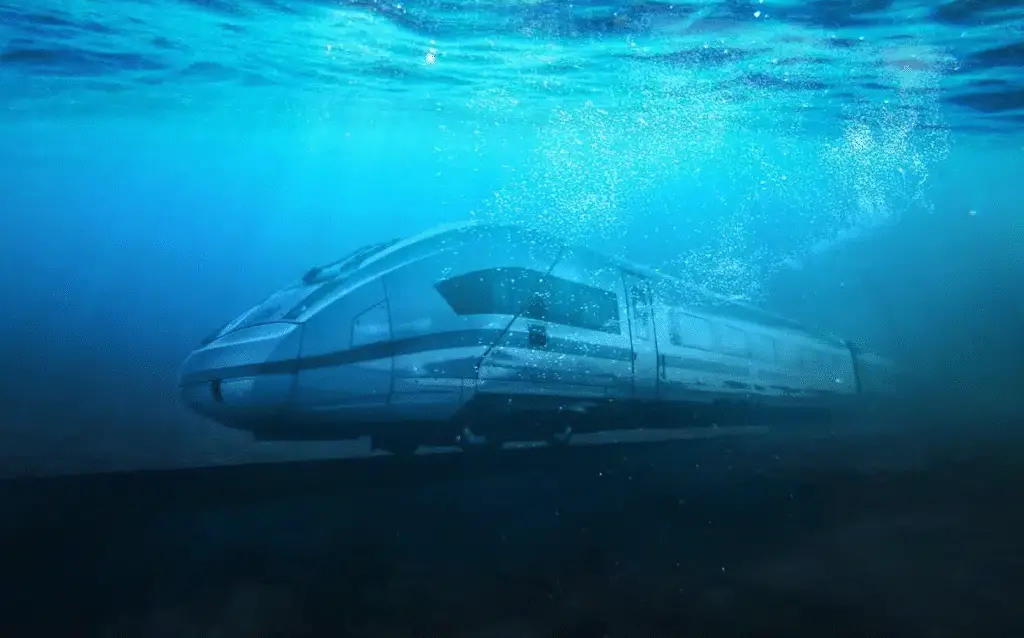

Watch: Top 5 underwater trains in the world

Could the “China-Russia-Canada-America” line face a similar fate?

The dream of an underwater train linking East and West captures the imagination, blending cutting-edge technology with a vision of global unity.

Yet, its challenges—geopolitical tensions, astronomical costs, and logistical complexities—cast a long shadow.

As China continues to push the boundaries of infrastructure, the world watches to see if this $200 billion dream will remain a blueprint or become a reality that redefines how we traverse the globe.

What would it take to turn this vision into tracks on the ground—or under the sea?