World’s Skinniest Animal: Defining What Makes an Animal the Thinnest on Earth

Defining Skinniness in Animals

In the animal kingdom, ‘skinniness’ encompasses more than just weight. Low body mass, minimal skeletal structure, and reduced body dimension relative to length all contribute to how scientists and biologists categorize ‘skinny’ animals.

Low body mass in some creatures reflects an evolutionary adaptation. The slender blind snake, often mistaken for a worm due to its thin, elongated body, exemplifies this trait. Its ‘skinniness’ allows it to move through soil and tight underground passageways with ease, evading predators and capturing prey.

Minimal skeletal structure adds another layer to the definition of skinniness. The barreleye fish boasts a largely cartilaginous skeleton, much reduced compared to other fish.

This adaptation minimizes its structural density, allowing it to thrive at extreme ocean depths where pressure would otherwise be unbearable.

On the dimension front, the Blackpoll Warbler is characterized by a delicate framework supporting considerable wingspan relative to its body size, enhancing its endurance for long transatlantic flights during migratory seasons.

The ghost shrimp exhibits an intriguing aspect of skinniness, with a thin, translucent structure serving as effective camouflage against predation.

Its slender claws are evolutionarily designed for efficient burrowing in sandy or muddy substrates at the ocean’s bottom.

These distinct attributes, rooted in niche adaptability, energy expenditure minimization, or camouflage, delineate how ‘skinny’ is characterized beyond ordinary smallness or lightness.

Such evolutionary adaptations underline the broader sphere of biodiversity and survival tactics.

Record-Holding Skinny Animals

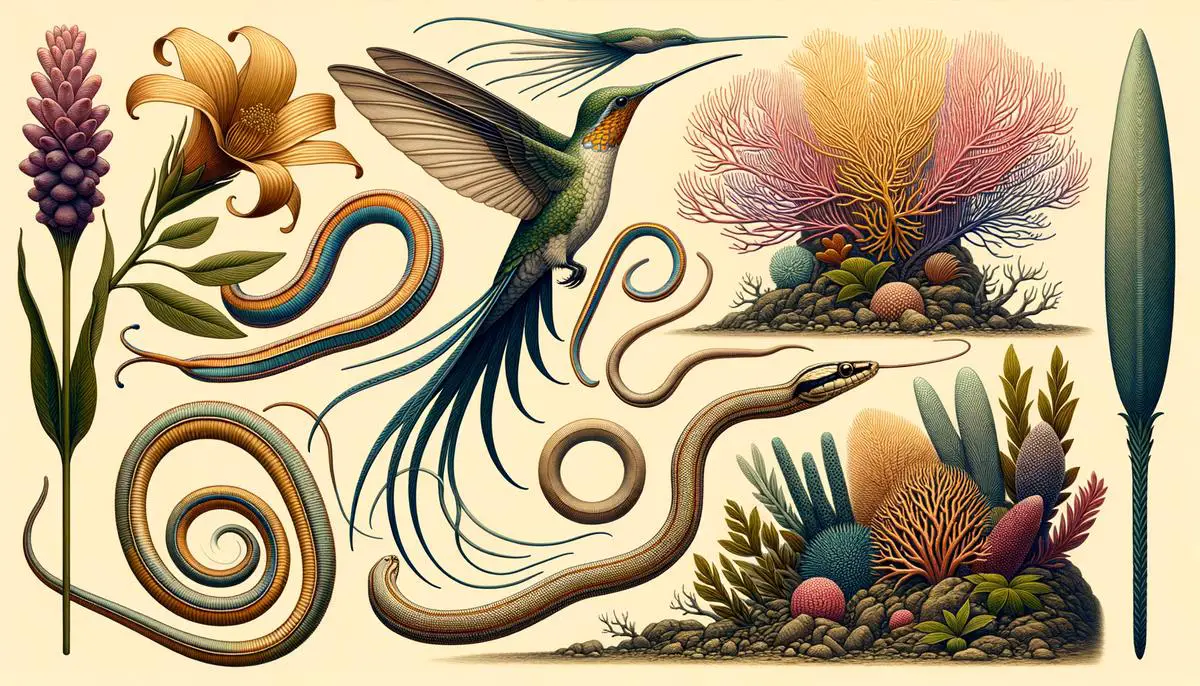

The bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae), often celebrated as the smallest bird, is also extremely slender in proportion to its feathered body. Found in Cuba, this avian marvel weighs less than two grams and measures a mere two to three inches in length.

Its slight dimensions suit its role as a proficient pollinator, maneuvering swiftly between flowers, compensating for its size with agility and energy efficiency.

The ribbon eel (Rhinomuraena quaesita) is another skinny titleholder. Its elongated, ribbon-like body provides a striking example of marine adaptability.

Native to Indo-Pacific oceans, this eel sports a continuous dorsal fin that aids in undulating swimming patterns crucial for snapping up prey in narrow reef crevices. Its slim morphology entails minimalist muscular structures designed to reduce drag―a vital adaptation for stealth and speed.

The thread snake (Leptotyphlops), scarcely thicker than spaghetti, has opted for a life underground where its cylindrical, slender body streamlines the burrowing process.

The limited circumference allows it to infiltrate soil and sand layers with minimal resistance, accessing areas larger predators can’t reach and capitalizing on unguarded insect larva for sustenance.

Biologically, skinniness across varied taxonomic groups often reflects ecological or physiological optimization. Birds like the bee hummingbird flaunt high metabolisms correlated with rapid wingbeats, necessitating minimized weight for aerial efficiency.

For marine species like the ribbon eel, skinny forms reduce water resistance, catering to an elegant propulsion system suitable for narrow reef exploration.

Environmental factors reveal equally potent influences shaping these skinny physiques. Adaptation and survival in physically constrained environments call for form factors that facilitate stealth, agility, and minimal energy expenditure—criteria impressively met by the slender designs of targeted species surviving in specialized habitats.

Adaptations and Survival

Skinny animals often exhibit higher metabolic rates, facilitating rapid energy utilization crucial for immediate responses to environmental challenges.

The bee hummingbird has one of the highest metabolic rates relative to its size, supporting its swift flight patterns. However, it also necessitates an almost incessant need for food intake.

Its days are spent in a continuous search for nectar and small insects, tailoring its feeding habits to be frequent and fast.

Predator evasion strategies present another facet of survival. The ribbon eel’s skinny body can quickly dart into narrow nooks of coral reefs, spaces predators larger than themselves cannot reach.

This offers a safe retreat and positions them perfectly to ambush unsuspecting prey. When aligned within the coral’s colorful backdrop, they become masters of camouflage.

For terrestrial animals like the thread snake, evading predators involves utilizing their minimalistic body size to access safe underground channels.

Their underground lifestyle reduces exposure to daytime predators and harsh climate conditions, optimizing survival with energy-conservative behaviors.

Skinny animals’ diets are meticulously aligned with resource availability and the energy cost of hunting or foraging. In many instances, lean diets are not just an outcome of evolutionary adaptation but also a necessity dictated by inherently high metabolic activities.

Ghost shrimps’ sandy burrow habitats dictate a diet heavy in microscopic organisms and detritus—abundantly available within their geographical niches while reducing exposure during food searches.

These evolutionary narratives underscore a broader ecological theme: adaptations are not just about survival but flourishing within a niche.

Each skinny creature, through its anatomical minimalist approach, provides answers to ecological queries, adding rich strands to the tapestry of life’s wide-ranging designs.

Conservation Challenges

Despite their ecological niche and fascinating adaptations, skinny animals face substantial conservation challenges that threaten their existence.

Habitat destruction, primarily driven by human activities like deforestation, urban development, and agriculture expansion, not only robs these creatures of their homes but also fragments their habitats into smaller, isolated patches.

This diminishes their ability to find food, mates, and shelter—critical resources for survival.

Climate change further escalates these challenges by altering the conditions of their fragile ecosystems. Changes in temperature and weather patterns can shift flowering and breeding seasons, directly impacting food availability and reproductive success.

For aquatic skinny animals, warming oceans and disrupted water currents affect coral reef health—a critical habitat where many species thrive.

Human interference, through pollution and recreational activities, intensifies stress on skinny animals. Pesticides can contaminate nectar sources, while noisy and intrusive tourist activities can disrupt natural behaviors and breeding success.

Light pollution also plays a role, disorienting species that rely on natural light cues for navigation and mating.

Despite these challenges, conservation efforts are budding across the globe. Specialized breeding programs and habitat restoration initiatives aim to buffer some of the risks, especially for endangered species.

Ecologists and conservationists are working to rehabilitate and conserve vital habitats that harbor a plethora of skinny species.

Research studies aimed at understanding the precise needs and behaviors of skinny animals have proved invaluable.

Advances in telemetry and miniaturized tracking devices have opened new doors to studying previously inaccessible aspects of their life histories, driving better-targeted conservation strategies.

Environmental awareness campaigns are gaining momentum, underscoring the link between local ecological actions and global biodiversity impacts.

By educating the public on the importance of these creatures beyond their size—highlighting their role in pollination, soil health, and ecological balance—conservationists are building broader support for environmental safeguards.

As scientific understanding deepens and extends to encompass a greater variety of life forms, the conservation narrative is expanding to include the small, skinny creatures whose roles might be oversized compared to their physical dimensions.

Each effort made in favor of protecting these creatures not only preserves their kind but also enforces the resilience of ecosystems worldwide.

The survival of skinny animals is not just about enduring but thriving through ingenious adaptations. Their slender forms are a testament to the resilience and ingenuity of nature, underscoring the importance of targeted conservation efforts to maintain the delicate balance of our ecosystems.

- Anderson JF, Rahn H, Prange HD. Scaling of supportive tissue mass. Q Rev Biol. 1979;54(2):139-148.

- Chai P, Dudley R. Limits to flight energetics of hummingbirds hovering in hypodense and hypoxic gas mixtures. J Exp Biol. 1995;198(Pt 11):2285-2295.

- Gans C. Biomechanics: An Approach to Vertebrate Biology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1974.

- Gillooly JF, Brown JH, West GB, Savage VM, Charnov EL. Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate. Science. 2001;293(5538):2248-2251.

- Pough FH. Amphibians and reptiles as low-energy systems. In: Aspey WP, Lustick SI, eds. Behavioral Energetics: The Cost of Survival in Vertebrates. Columbus: Ohio State University Press; 1983:141-188.