Shot 8 times by her own family: Rukhsana Bibi’s fight against honour killings in Pakistan

- Rukhsana Bibi, a young Pakistani woman, miraculously survived an honour killing attempt in 2013 after being shot eight times by relatives furious over her love marriage.

- Defying deep-rooted patriarchal traditions in Kohistan, she has emerged as a vocal advocate, pursuing legal action amid death threats and highlighting systemic violence against women.

- Her case underscores Pakistan’s ongoing human rights crisis, where honour killings claim over 1,000 lives annually, fueling calls for stronger enforcement of anti-gender violence laws.

Islamabad, Pakistan – In the stifling heat of a late August night in 2013, Rukhsana Bibi stirred from sleep in the courtyard of her modest mud-brick home in Akora Khatak, a remote town nestled near the rugged mountains of Kohistan in northwestern Pakistan.

The 18-year-old, who had dared to choose love over family dictate, heard unfamiliar footsteps echoing through the darkness.

Before she could fully comprehend the intrusion, shadows loomed over her and her husband, Mohammad Yunus.

Gunfire erupted, shattering the quiet village air. But how did a simple village wedding lead to this moment of terror, and what hidden forces drove her own kin to such brutality?

It all began two years earlier, at a joyous family wedding in the summer of 2011.

Amid the vibrant dances and celebrations typical of Kohistan’s tribal communities, Rukhsana locked eyes with Yunus, a 22-year-old medical technology student from a nearby village.

Their connection was instant, but in a region governed by strict honour codes—where any unsupervised interaction between unrelated men and women is deemed a grave insult to family prestige—it was also forbidden.

They exchanged phone numbers secretly, nurturing their bond through hushed calls and messages on mobile devices that were becoming increasingly common even in isolated areas.

As their affection deepened, Rukhsana faced mounting pressure from her conservative family, led by her father, an imam known for his rigid adherence to tribal customs.

By April 2013, her relatives had arranged her marriage to an uneducated cattle herder, a first cousin, in line with prevalent endogamous practices aimed at preserving lineage and property.

Refusing to submit, Rukhsana made a bold escape on the day of her 10th-grade biology exam, still clad in her school uniform.

She and Yunus fled to Peshawar, where they exchanged vows in a quiet ceremony, embracing a love marriage that defied the entrenched norms of their Pashtun heritage.

“We knew my family were chasing me. We knew they wouldn’t leave us alone. This is their law,” Rukhsana later recounted, her words capturing the inescapable shadow of retribution that haunts many women in similar situations.

For four months, the couple lived in fragile peace, hiding in Akora Khatak while Yunus worked odd jobs to support them.

Rukhsana, once a top student aspiring to become a doctor, adapted to her new reality, even discovering she was pregnant—a beacon of hope amid uncertainty.

Yet, in Kohistan, where tribal jirgas (councils of elders) often operate parallel to state law, perceived slights to family honour are met with swift, unforgiving violence.

Honour killings, locally termed karo-kari, stem from a medieval code that views women as bearers of familial reputation.

Any suspicion of impropriety—real or imagined—can justify murder, with the woman’s family obligated to strike first to “cleanse” the shame.

That fateful night, the attackers—allegedly including Rukhsana’s father, uncle, and cousins—scaled the compound wall under cover of darkness.

They targeted Rukhsana first, as custom demands, firing relentlessly.

Bullets tore through her body: two pierced her chest, three shredded her left leg, and three more lodged in her left hip.

Yunus, awakening to her screams, lunged to shield her but was gunned down with 11 shots to his arms, legs, and chest.

As blood pooled around them, Rukhsana played dead, her mind racing with thoughts of their unborn child.

The assailants, satisfied with their “justice,” vanished into the night. But in those agonizing minutes, as Yunus gasped his final breaths beside her, did she dare hope for survival—or was this the end of her defiance?

Neighbors, alerted by the commotion, rushed in 15 minutes later, finding Rukhsana barely conscious amid the carnage.

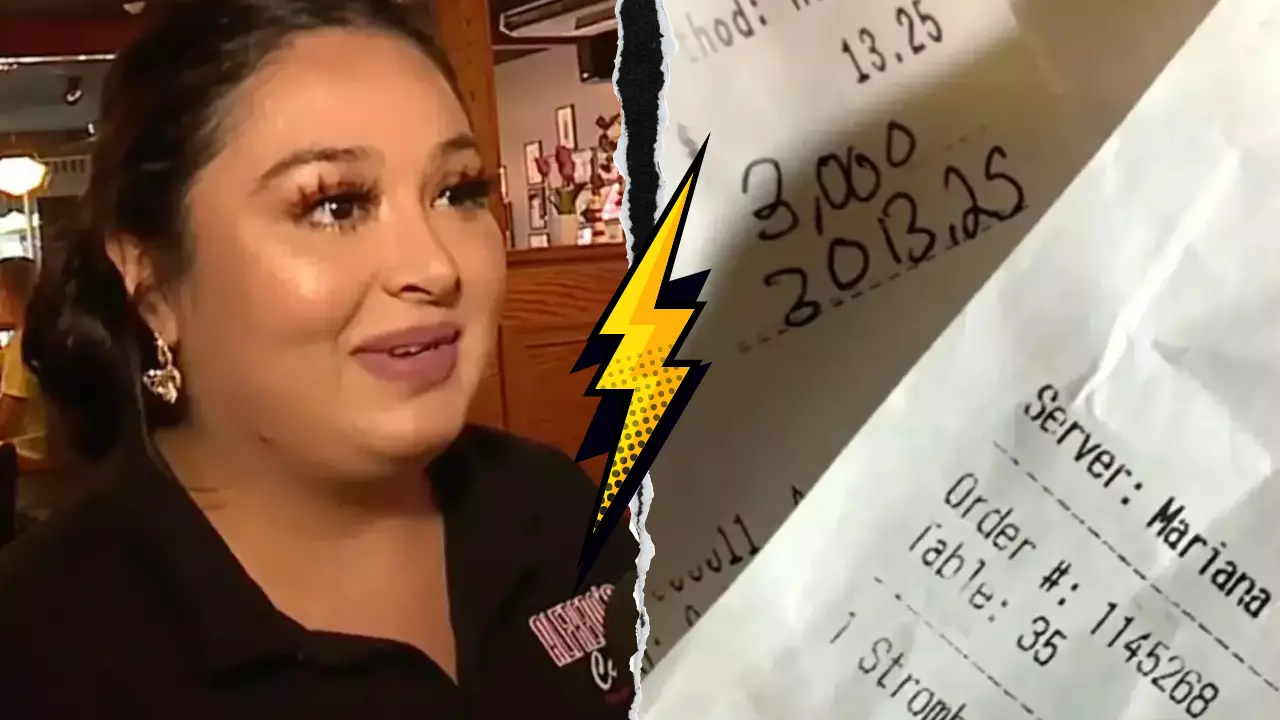

Rushed to a nearby hospital, she underwent emergency surgeries to remove the bullets and stabilize her wounds.

The physical toll was immense: severe damage to her lungs and limbs left her reliant on a walking frame, with recurring weakness plaguing her daily life.

Tragically, the trauma induced complications in her pregnancy; the baby, born severely disabled shortly after, succumbed just one day later.

In the hospital’s sterile halls, as doctors fought to save her, Rukhsana grappled with an even deeper wound—the loss of her husband and child, and the betrayal by her blood relatives.

What would compel a father to turn executioner against his own daughter?

Kohistan’s isolation exacerbates such atrocities. Spanning vast mountainous terrain in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the area is marked by low literacy rates, especially among women, and a reliance on subsistence farming and herding.

Mobile technology, while connecting lovers like Rukhsana and Yunus, has paradoxically fueled a spike in honour-related violence, as families react to perceived erosions of control.

According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, over 470 honour killings were documented in 2023 alone, though activists estimate the true figure exceeds 1,000 annually, with many cases unreported or disguised as suicides.

Amnesty International reports that victims span all ages and regions, often killed for eloping, refusing arranged marriages, or even unfounded rumors.

In this patriarchal stronghold, women like Rukhsana are seen not as individuals with rights, but as symbols of family honour to be protected—or eliminated.

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Birth Year and Age at Attack | Born circa 1995; 18 years old during the 2013 assault |

| Meeting with Husband | Summer 2011 at a village wedding in Kohistan |

| Elopement and Marriage Date | April 2013; vows exchanged in Peshawar |

| Attack Location and Date | Akora Khatak, near Kohistan; late August 2013 |

| Injuries Sustained | Shot 8 times: 2 in chest, 3 in left leg, 3 in left hip |

| Husband’s Injuries | Shot 11 times; died at the scene |

| Pregnancy Outcome | Baby born disabled post-attack; died one day later |

| Legal Developments | Identified attackers; warrants issued in 2014; no arrests by 2019 |

| Broader Impact | Contributed to 2016 Anti-Honour Killing Law in Pakistan |

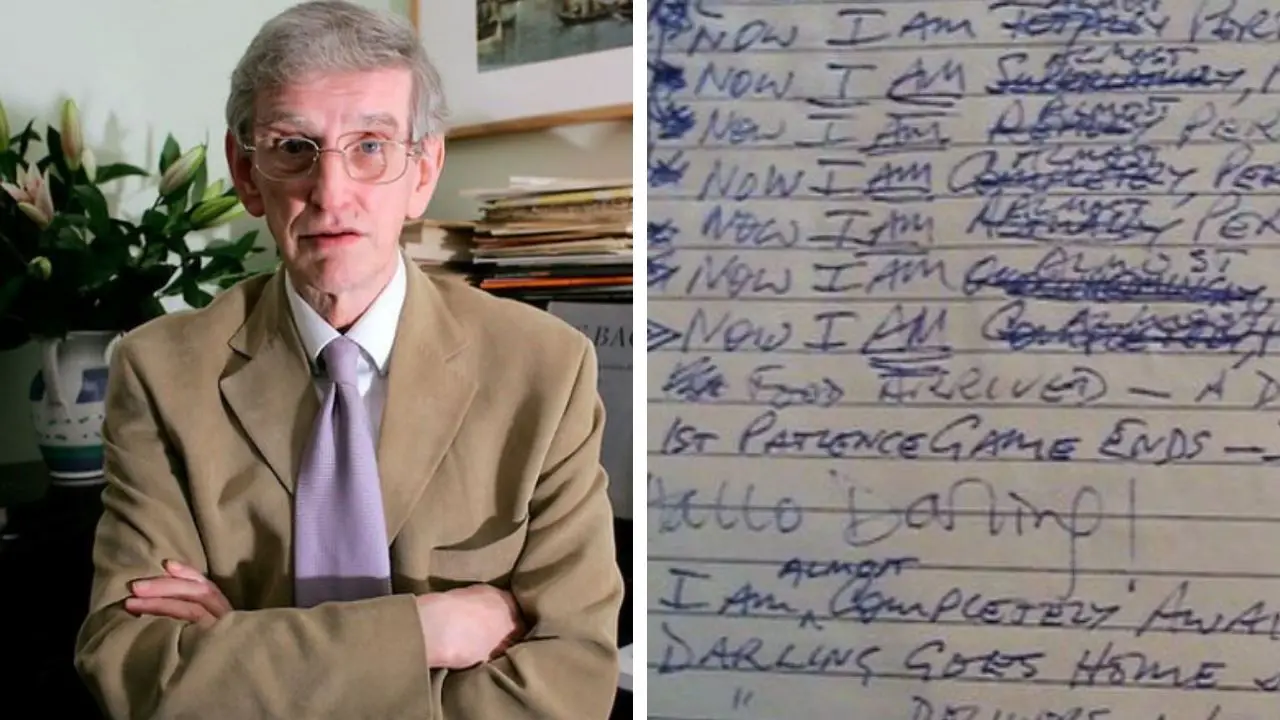

Emerging from the brink of death, Rukhsana chose an extraordinary path: public defiance.

Unlike most survivors who vanish into silence or succumb to pressure, she spoke out to media outlets, detailing her ordeal with a steady voice despite tears.

“I had no choice. I either had to kill myself, or run away,” she said, her resolve steeling against the cultural taboo of challenging family.

Filing a police report, she named five relatives as perpetrators, leading to arrest warrants in 2014.

Yet, justice proved elusive—one suspect was acquitted for lack of evidence, another deemed innocent, and three fled, evading capture in the region’s treacherous forests and caves.

Police, stretched thin over 70-80 square kilometers per station, often arrive too late, warned by villagers loyal to tribal bonds.

“Fighting such a case in the court is tough, but when I go for hearings, I don’t feel any pain in my body.”

“I am a dead person anyway, but I have to get justice for myself and my husband. We did no wrong,” Rukhsana declared, her words echoing a rare courage.

Her battle coincided with national shifts. The 2016 Anti-Honour Killing Law, spurred by high-profile cases like social media star Qandeel Baloch’s murder, mandated life imprisonment for perpetrators and closed forgiveness loopholes by families.

Yet, enforcement lags; convictions remain rare due to manipulated evidence and judicial hesitance.

Activist Farzana Bari notes that rising tech use among young women has intensified backlash, with families resorting to extreme measures to reassert dominance.

Rukhsana’s story gained international attention, amplifying calls for reform, but she paid dearly—living in hiding, haunted by death threats from kin who view her survival as unfinished business.

Fast-forward to 2025, and the scourge persists. A viral video from Balochistan captured the execution of a couple accused of an affair, ordered by a tribal leader, sparking nationwide outrage and leading to 13 arrests.

In Rawalpindi, 18-year-old Sidra Bibi was slain on jirga orders by her father and ex-husband, with nine detained amid public fury.

Earlier this year, in Lahore, two brothers allegedly killed their mother and sister over honour suspicions.

These incidents, echoing Rukhsana’s nightmare, reveal a grim pattern: despite laws, cultural inertia and weak prosecution perpetuate the cycle.

Rukhsana, now in her late 20s, continues her court appearances, frail but unbowed, demanding the dismantling of tribal laws that ruin lives.

“I demand that this tribal law should be abolished. It ruins dozens of lives, young boys and girls, who also have no happiness or choice of how to spend their own lives,” she urged.

But as threats mount and her case drags on without resolution, one question lingers: will her unyielding spirit finally shatter Pakistan’s deadly honour code, or will the next bullet find its mark?