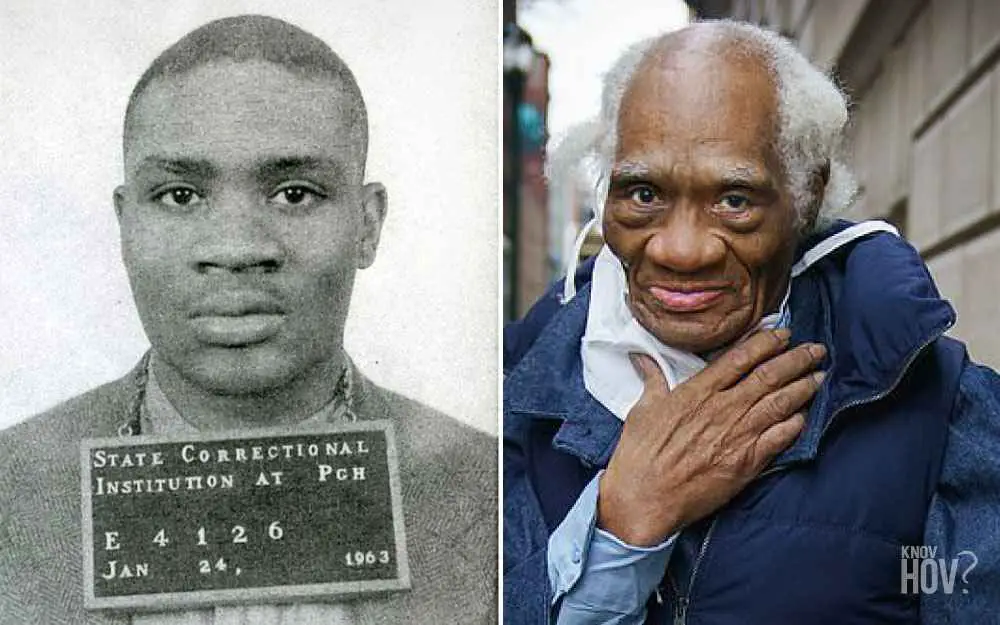

Joseph Ligon was released after serving the 5th longest prison sentence in recorded history (67 years, 54 days)

- Joseph Ligon, sentenced to life without parole at just 15 for a 1953 Philadelphia stabbing spree, became a symbol of flaws in the juvenile justice system after refusing parole multiple times to fight for full exoneration.

- His release on February 11, 2021, at age 83 marked the end of one of the longest prison sentences in recorded history, spotlighting ongoing debates over mass incarceration and criminal justice reform.

- Ligon’s story highlights the human cost of mandatory life sentences for minors, influenced by landmark Supreme Court rulings that reshaped true crime narratives around redemption and rehabilitation.

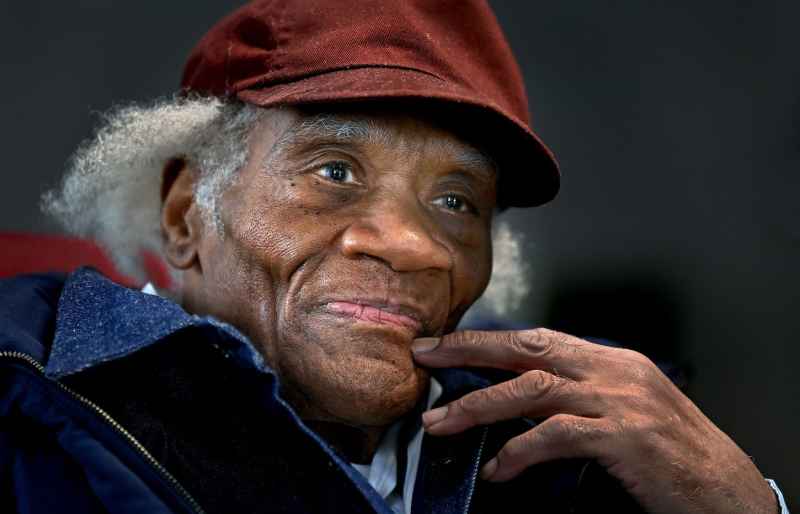

In the crisp air of a Pennsylvania morning, an 83-year-old man stepped out of the State Correctional Institution Phoenix, his eyes adjusting to a world transformed by decades of change.

Joseph Ligon, clad in a simple coat provided by his supporters, tasted freedom for the first time since the Eisenhower era.

But what led this elderly figure, once a wide-eyed teenager from Alabama, to endure such an extraordinary ordeal in the annals of American criminal history?

Ligon’s journey began in the segregated South, where he was born in 1937 and raised by his grandparents in Birmingham.

At 13, he relocated to Philadelphia to join his parents—a nurse mother and mechanic father—along with his siblings in a modest blue-collar neighborhood.

School proved challenging; illiterate and socially withdrawn, he avoided crowds and sports, forming few bonds beyond family. By 15, however, a fateful night altered everything.

On February 20, 1953, while out with four other teens, what started as panhandling for wine money escalated into a chaotic robbery and stabbing incident across South Philadelphia streets.

Six people were wounded, and two—Charles Pitts and Jackson Hamm—lost their lives in the frenzy.

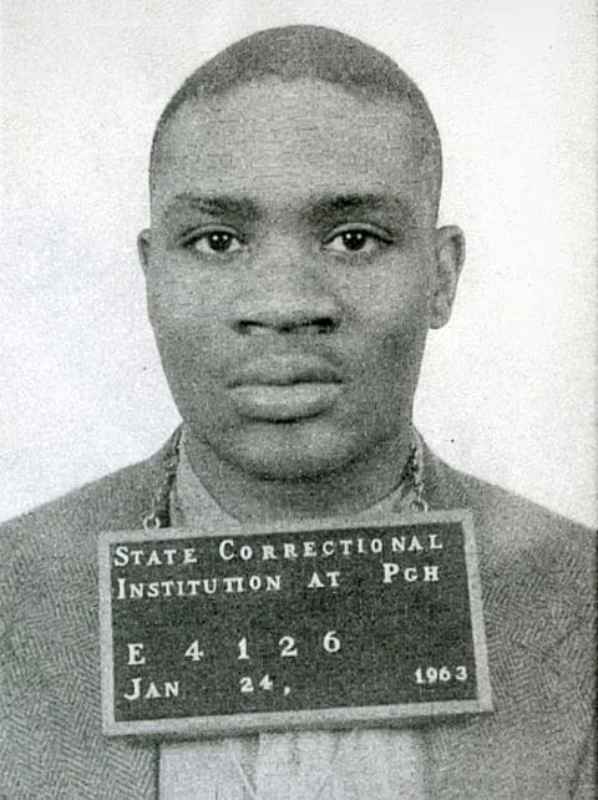

Arrested swiftly as the first suspect, Ligon was detained at a distant police station, isolated for five days without legal counsel.

His parents were denied visits, fueling his early sense of injustice. Charged with two counts of first-degree murder, he pleaded guilty in a degree-of-guilt hearing, admitting to stabbing one survivor but steadfastly denying any killings.

Under Pennsylvania law at the time—one of only six states mandating life without parole for such convictions—he received the automatic sentence on December 18, 1953.

Unaware of the full implications, he recalled later, the gravity hit only gradually as years turned into lifetimes behind bars.

Transferred initially to facilities ill-equipped for juveniles, Ligon adapted to a regimented existence that would define his next six decades.

He cycled through six prisons, including stints at Eastern State Penitentiary’s remnants and modern complexes like SCI Graterford.

Daily life revolved around 6 a.m. wake-ups for headcounts, breakfast at 7, and labor from 8 onward.

He toiled in kitchens, laundries, and primarily as a janitor, earning a reputation for diligence and avoidance of conflict.

“Mind your business, always try to do what’s right,” he would advise, steering clear of drugs, alcohol, or escape plots that ensnared others.

Solitude became his sanctuary; he requested single cells throughout, embracing loner status amid the cacophony of incarceration.

Family visits dwindled as loved ones passed—his parents, brother, and sister all died during his imprisonment, leaving him without external ties.

Yet, hope flickered. In the 1970s, parole offers emerged, but Ligon rejected them, viewing supervision as another chain.

“I’m a grownup now,” he asserted in later interviews, refusing to accept terms that undermined his dignity.

The turning point arrived with evolving juvenile justice precedents. In 2005, the Supreme Court banned executions for minors, sparking reviews of life sentences.

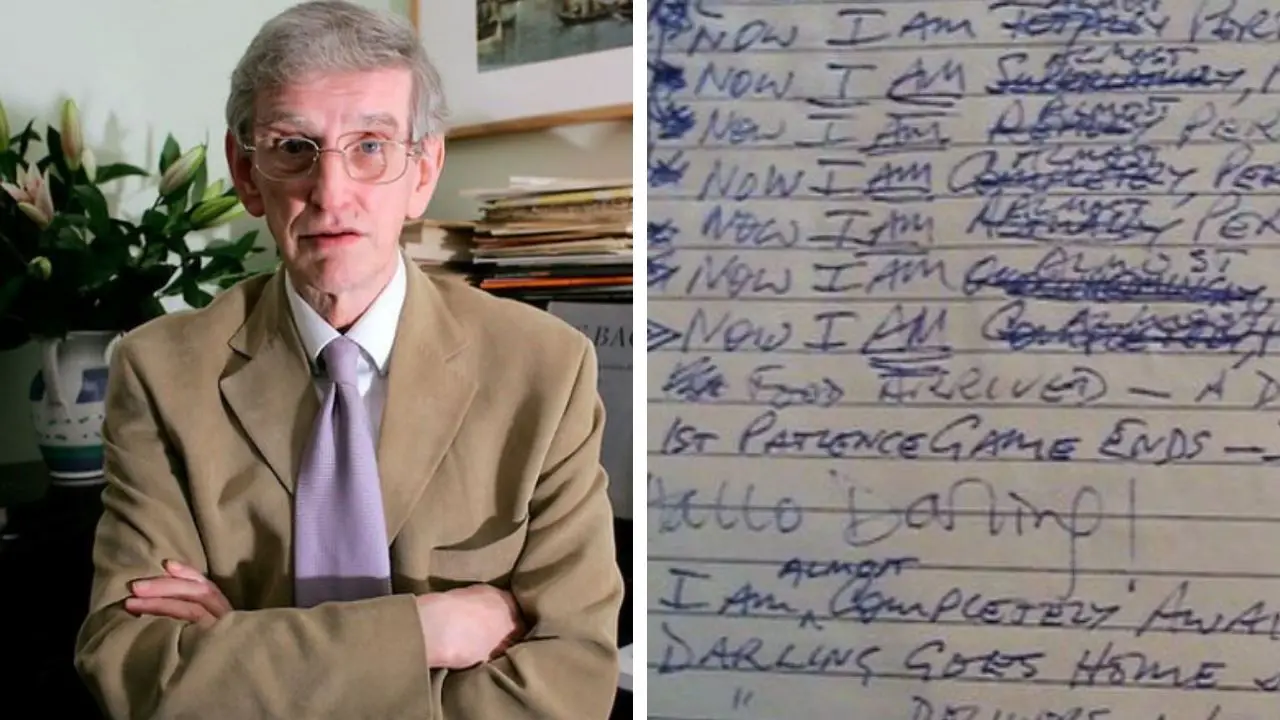

Attorney Bradley Bridge, from Philadelphia’s Defender Association, discovered Ligon’s case in 2006, 53 years into his term.

Shocked by Ligon’s optimism despite ignorance of his sentence details, Bridge noted his client’s unwavering belief in eventual release.

A 2012 ruling in Miller v. Alabama deemed mandatory life without parole for juveniles unconstitutional, made retroactive in 2016’s Montgomery v. Louisiana.

This opened doors for over 500 Pennsylvania juvenile lifers, including Ligon.

Resentenced in 2017 to 35 years to life, he qualified immediately for parole but declined again, insisting on unconditional freedom.

Bridge escalated the fight to federal court, arguing the resentencing violated constitutional protections.

In November 2020, U.S. District Judge Anita B. Brody ruled in favor, ordering resentencing or release within 90 days.

Prosecutors, led by then-District Attorney Larry Krasner, opted not to oppose, aligning with reform efforts amid national reckonings over racial disparities in sentencing—Ligon, a Black man convicted in a pre-civil rights era, embodied such inequities.

As release neared, curiosity builds: How would a man frozen in 1950s time navigate smartphones, skyscrapers, and societal shifts?

Picked up by Bridge on that February day, Ligon’s reaction was understated—no jubilant outbursts, just quiet absorption.

“Like being born all over again,” he described, marveling at sleek cars and towering buildings during the drive to a halfway house run by the Pennsylvania Prison Society.

Reentry coordinator John Pace, himself a former juvenile lifer freed after 31 years, guided Ligon’s transition.

Simple joys emerged: his first cellphone, a taste of modern cuisine, and interactions with younger generations.

Yet challenges loomed—health issues from aging in confinement, including potential undiagnosed conditions from limited medical access, and psychological scars from isolation.

Ligon expressed remorse for the victims’ families, acknowledging the irreversible harm while maintaining his limited role in the deaths.

His story intersects with broader true crime discussions, where cases like his fuel advocacy for ending life without parole for youth, citing brain development science showing teens’ impulsivity.

Organizations like the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth hail him as a beacon, with over 2,500 juvenile lifers nationwide affected by similar rulings.

But what drove Ligon’s refusal of parole, prolonging his own suffering? Principle, he insists, rooted in a belief that accepting oversight equated to admitting defeat.

Midway through this saga, key milestones stand out:

| Key Fact | Details |

|---|---|

| Birth Year | 1937 |

| Age at Crime | 15 |

| Crime Date | February 20, 1953 |

| Victims | 8 stabbed; 2 killed (Charles Pitts, Jackson Hamm) |

| Sentence Date | December 18, 1953 |

| Original Sentence | Mandatory life without parole |

| Prisons Served In | 6, including SCI Phoenix and Graterford |

| Jobs in Prison | Kitchen worker, laundry, janitor |

| Supreme Court Rulings Impacting Case | Miller v. Alabama (2012), Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016) |

| Resentencing | 2017: 35 years to life |

| Federal Ruling | November 2020: Unconstitutional; release ordered |

| Release Date | February 11, 2021 |

| Duration Served | 67 years, 54 days |

| Age at Release | 83 |

| Post-Release Support | Pennsylvania Prison Society halfway house |

This timeline underscores the protracted battle, but Ligon’s post-release life reveals even more layers.

Settling into Philadelphia’s familiar yet alien streets, he aimed to mentor at-risk youth, sharing warnings about street life’s perils.

“I got caught up,” he reflected, hoping his narrative prevents similar fates.

Interviews, like his CBS appearance, showcased a man transformed—not bitter, but philosophical, crediting prison for teaching humility.

Yet, whispers of unfinished business persist. Ligon pondered reconnecting with distant relatives, exploring hobbies never pursued, and perhaps authoring a memoir to detail untold prison anecdotes.

Advocates push for compensation laws, noting Pennsylvania’s lack of payouts for wrongful or excessive incarcerations, leaving him reliant on donations.

His case echoes others, like the Central Park Five, amplifying calls for restorative justice.

Watch: After serving 68 years in Pennsylvania prison, Joe Ligon returns to modern world he barely knows

As days turned to months, Ligon adapted remarkably, learning public transit and enjoying parks—small freedoms magnifying his resilience.

But one question lingers, drawing deeper into his enigma: In a system designed to break spirits, how did he emerge unbroken, ready to embrace “a better everything”?

His answer, delivered with quiet conviction, hints at an inner strength forged in solitude, challenging perceptions of guilt, punishment, and second chances.

And as he walks Philadelphia’s sidewalks, one wonders what revelations his future steps might uncover in this ongoing chapter of redemption.